McLaren's teammate Jack Brabham had a slightly rougher last lap. Archived footage shows him running out of gas and then pushing his car across the line in fourth place at Sebring, the final race of the Formula One season. Brabham held on to his narrow points lead in the F1 standings and locked up the Formula One Drivers' Championship in spite of the mishap.

The messy finish marked the last time a Formula One lap would be run in the Sunshine State for more than 60 years.

After mass-media conglomerate Liberty Media acquired Formula One (now better known as Formula 1 or F1) in 2016, a campaign to bring F1 competition back to Florida made headway. Formula 1 set about working with Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross to find a long-term home for races in the Miami area.

The effort was not without controversy, as many Miamians opposed Formula 1's return, citing concerns over excessive noise and pollution. Three years of negotiations, political wrangling and litigation ensued; meanwhile, claims of ethics breaches were lobbed against then-County Mayor Carlos A. Giménez in connection with his vetoes of commission votes linked to Formula 1. Giménez, now a U.S. Congressman, denied any wrongdoing and said his actions were cleared by county ethics staff.

Formula 1 ultimately inked a ten-year deal under which it will hold annual championship races in Miami Gardens and provide the northwest Miami-Dade municipality with $5 million in community benefits. The inaugural Miami Grand Prix race will be run on Sunday, May 8, at Hard Rock Stadium, where the grounds have been converted into a racing complex lined with high-priced club seating, a makeshift yacht marina, and a pool area complete with two stories of cabanas. In step with Miami's recent push to attract cryptocurrency-linked investment, the title sponsor is Crypto.com.

Embed from Getty Images

The track has three straightaways and 19 corners, with early estimates of top speeds approaching 200 mph. Formula 1 is touting its hand in the course design, describing the circuit as a "dynamic and free flowing track." (A planned section of the track that extended onto public streets outside the stadium was nixed in hopes of quelling outcry from Miami Gardens residents.)

Memory Lane

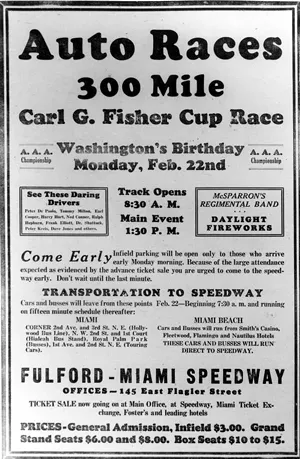

Miami's open-wheel racing history dates back nearly a hundred years, to the construction of the Fulford Miami Speedway by real estate developer and racing enthusiast Carl Fisher. Completed amid the 1920s South Florida real estate boom, the wood track in North Miami Beach played host to a 300-mile race in February 1926 that attracted as many as 20,000 people. Fisher, who had helped develop an early incarnation of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, believed the Fulford track would make Miami a global auto-racing hub.

An announcement for the one and only race held at Carl Fisher's Fulford-Miami race track in North Miami Beach

Photo by G.W. Romer via floridamemory.com

"It was nothing but a Miami of spectacle — to bring tourists, to bring investors in this inflated real estate scene. In the '20s, it was crazy. Miami, Greater Miami, was already an outstanding tourist destination that offered all kinds of events — horse racing, dog racing, football games," George elaborates.

The Great Miami Hurricane of September 1926 wiped out the track, along with countless other South Florida developments. The storm was one of the final blows to the local real estate bubble, which had been teetering on the brink owing to a railroad supply-chain crisis.

"In some ways, [the 1926 race] was in the area of that last gasp. That boom was beginning to decline and buyers were beginning to back away," George notes. "And one of the mindsets was, 'We need to continue to provide spectacles to bring people down here for reasons of tourism and investment."

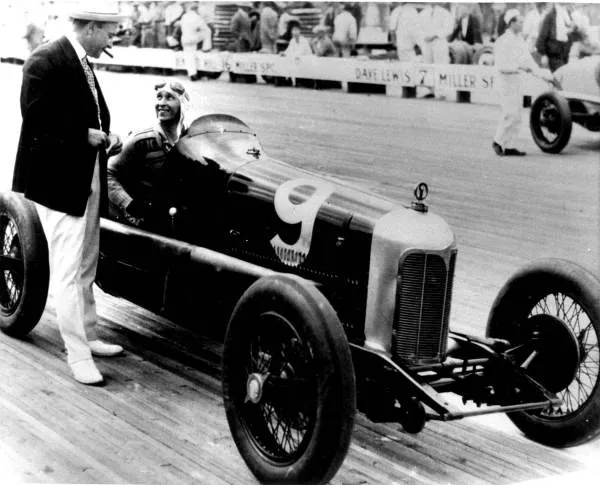

Fulford-Miami official starter Barney Oldfield with driver Ralph Hepburn on February 22, 1926

Photo courtesy of floridamemory.com

Community Outcry

By the time Liberty Media closed its roughly $4.6 billion acquisition of Formula 1 in 2016, a planned expansion of F1 events in the United States was well underway.Prior to the acquisition, longtime F1 chief executive Bernie Ecclestone had been publicly discussing negotiations to schedule a race in Las Vegas. And Formula 1 had long been looking to expand on a successful run of races in Austin, Texas, the site of its only stateside event at the time.

Salvaged lumber from the Fulford-Miami grandstand was reportedly used to rebuild the city after the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926.

Photo courtesy of floridamemory.com

Chase Carey, who took the helm of Formula 1 following the acquisition, revealed in 2017 that F1 would seek to set up new U.S. racing circuits in "destination cities" — areas that could attract tourists from around the globe and keep them busy for an entire week. "The race will remain the center of the event, but overall it will be more than just a Formula 1 weekend," Carey promised.

As a tropical tourist hotspot with a penchant for entertainment spectacles and a track record of accommodating high-level sporting events even amid controversy, South Florida evidently fit the bill.

In May 2018, Formula 1 confirmed that it was eyeing downtown Miami as the site of the first F1 race in Florida in decades. Negotiations began ramping up between Miami-Dade County, Formula 1, and Dolphins owner Ross, a real estate developer who made his fortune as founder of the global firm the Related Companies.

Complicating matters for the county, however, Mayor Giménez's son was serving as a lobbyist for Formula 1, according to court documents. In mid-2018, Giménez purportedly recused himself from issues surrounding F1.

Formula 1 backed off plans to run a race in downtown Miami after a group of residents hired lawyers and sent a cease-and-desist letter to the city. The focus then shifted to holding the race at the Dolphins' Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens, a venue with a history of hosting Super Bowls, musical concerts with massive attendance, and countless other high-profile events.

Like the downtown Miami denizens before them, many Miami Gardens locals mounted opposition. At public meetings, they complained they were burnt out from a never-ending stream of large-scale events at the stadium, and that the planned Miami Grand Prix would be the proverbial final straw. Bringing annual F1 races to Miami Gardens, they argued, would be akin to hosting a Super Bowl every year in terms of traffic gridlock and community disruption.

Oliver Gilbert, Miami Gardens' mayor at the time, echoed the concerns at a county meeting.

"This has to be a good place to live...not just visit. Formula 1 will bring in people, but the people who live here matter," Oliver said.

In response to the community outcry, the county commission passed a resolution in October 2019 that heavily regulated auto racing events. The measure required noise and pollution studies for certain racing events and prohibited auto racing-related street closures in residential areas.

Giménez, despite having previously recused himself from Formula 1 matters, vetoed the race restrictions. He denied any conflict of interest, pointing to a county ethics board decision noting that his son was no longer working as a lobbyist for Formula 1.

Lawsuits were later filed against Giménez, the county, the Dolphins, and Hard Rock Stadium (among others), in an attempt to stop the Miami Grand Prix. The plaintiffs, former county commissioner Betty Ferguson among them, alleged that the move to host the race in Miami Gardens, a predominantly Black neighborhood, was an act of discrimination.

The plaintiffs also accused Giménez of improperly accepting Super Bowl tickets from Ross in the midst of the controversy.

"During the time that Mayor Giménez was publicly threatening to veto any action by the County Commission relating to F-1 racing in Miami Gardens, [he] accepted two Super Bowl tickets from Stephen Ross worth $8,000," a group of Miami Gardens residents alleged in a federal lawsuit. (Giménez maintains he did nothing wrong and that he received clearance from ethics counsel to accept the tickets. He purportedly repaid Ross for one of the tickets.)

A judge rejected the plaintiffs' federal case in June 2021, and the Miami Grand Prix moved ahead into the track-construction phase.

Still pending is a county court lawsuit, however, in which residents claim the engine noise generated by the Miami Grand Prix will violate local ordinances and pose a risk of hearing damage. A judge declined to issue a ruling before the May 8 race but is allowing the case to move forward so that the residents can challenge future races in court.

Samuel Dubbin, an attorney in the county case, tells New Times that blame has been unfairly laid at his clients' feet under the pretense that they moved into the area after the stadium was constructed and should have known about traffic gridlock and noise issues around the venue.

"It's offensive for the Dolphins or the city to argue that people who have lived there for generations could have known better," Dubbin says, noting that many of his clients bought their homes before the stadium existed. "The county and the Dolphins shoved that stadium down residents' throats and used the political and economic power they had to just pulverize the residents.""The county and the Dolphins shoved that stadium down residents' throats." —attorney Samuel Dubbin

tweet this

Throughout the dispute, the Miami Dolphins and Hard Rock Stadium have maintained that Formula 1 racing will be a boon for the community, not a burden. Their camp estimates that the Miami Grand Prix will generate a $400 million economic impact, along with 4,000 jobs.

Race organizers say early concerns over the Grand Prix's impact on Miami Gardens have been addressed by building a sound wall, ensuring races don't run during school hours, and eliminating track elements on public roads.

Formula 1 Down the Road

The Miami Grand Prix comes at a critical moment for Formula 1 in the United States, as the brand's popularity is rapidly growing stateside. ESPN's average ratings for the 2021 F1 season grew more than 50 percent year over year. Viewership is spiking even further this year, with races from the 2022 season raking in some of the highest-ever F1 cable ratings in the United States.In March, Formula 1 announced that a race in Las Vegas would be added in 2023 — making it the first year since the early 1980s that three U.S. races will be held in a single season.

On the track, Red Bull Racing's team is looking to re-establish dominance in the sport after watching its rival Mercedes win the team championship every year since 2014. Red Bull had a strong run prior to that, locking up Constructors' Championships from 2010 to 2013. But it struggled to keep pace with Mercedes after Formula 1 instituted sweeping engine-design changes the following year.

The 2021 season saw the F1 championship come down to the final race, the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix. Red Bull's 24-year-old wheelman Max Verstappen beat out seven-time F1 champion Lewis Hamilton of the Mercedes team on the heels of a controversial restart prompted by a late-race crash. Going in, the men were tied in the points race, and Verstappen's win secured him the driver's championship. (Mercedes edged Red Bull for the team championship).

Journalist and author Maurice Hamilton says that beyond the intrigue surrounding Red Bull's resurgence, the rising popularity of F1 in the United States can be attributed to Liberty Media's "more open outlook about how Formula 1 should be promoted."

In addition to F1, Liberty Media owns the Atlanta Braves, SiriusXM Satellite Radio, and event promoter LiveNation, among other assets. (The company is controlled by John Malone, a self-described libertarian who is one of the largest private landowners in the United States. He served as an electrical engineer at Bell Laboratories in the 1960s before taking a CEO position with cable company Tele-Communications Inc. and rising into the ranks of the nation's wealthiest media executives.)"Drive to Survive has given Formula 1 a human face. The timing of the Miami Grand Prix is perfect from that point of view."

tweet this

Before the Liberty Media buyout, Ecclestone was credited with tightening up the brand and helping F1 grow into a multibillion-dollar sport with global TV viewership. But according to Hamilton, Ecclestone strove to keep the politics and inner workings of Formula 1 out of the public eye.

"[Prior to the acquisition], film cameras had to pay a fortune to get in to film anything," Hamilton says. "Liberty Media has opened it right up. And they've encouraged people to come and film."

Under Liberty Media's ownership, Formula 1 authorized the popular Netflix series Drive to Survive, which has helped popularize the European-dominated F1 among American audiences, Hamilton says. The series includes in-depth interviews with team members and chronicles behind-the-scenes drama and midrace antics.

"They have unlimited access to the teams. In the days of Bernie Ecclestone, that would be unheard-of, simply would not be allowed," Hamilton surmises. "It has given Formula 1 a human face, which it didn't really have before."

Adds Hamilton: "The timing of the Miami Grand Prix is perfect from that point of view."