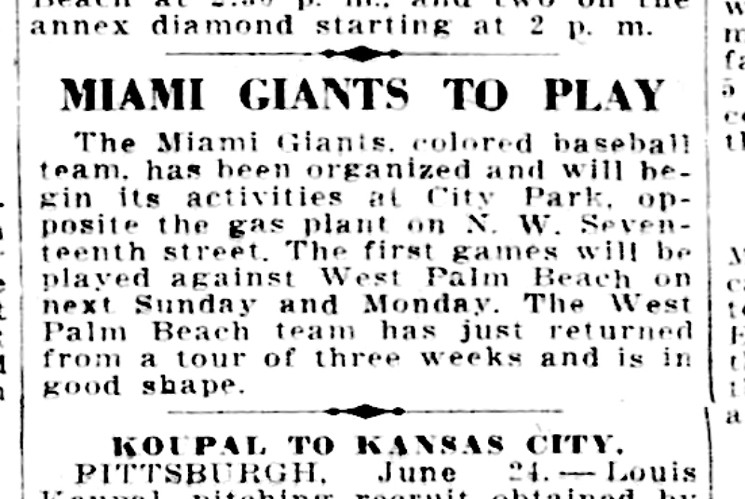

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the formation of the Negro Leagues. Until 1947, when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers and broke the color line, baseball was a segregated sport. White ballplayers had Major League Baseball as we know it today, and Black ballplayers had the Negro Leagues: an appellation given in 1920 to a consortium of Black baseball leagues after the creation of the Negro National League. Though 1920 is designated as the inaugural year, the Negro Leagues teams had been competing against each other since the late 19th century.

South Florida was a hub of Black baseball. Players came down seasonally, working in hotels as bellmen and busboys, and sometimes even playing in the Florida Hotel League on teams sponsored by the very hotels they worked at. One of the great players in baseball history, Oscar Charleston, played for both the Royal Poinciana Hotel and the Breakers Hotel teams in Palm Beach. In his book I Was Right on Time, John James "Buck" O'Neil wrote about playing in front of fans at Dorsey Park for our local team: the Miami Giants.

O'Neil wrote about how the team was "owned by two bootleggers" and how "you couldn't afford to be too picky about whom you played for, because a lot of clubs were owned by men who ran numbers rackets and booze." It was Miami, after all.

The Giants were formed and "financed in the late 1920s by a local black bootlegger and numbers king, Johnny Pierce," according to Raymond Mohl's 2002 article in Tequesta, the literary journal published by HistoryMiami. Little else is written about Pierce, who died in 1937 shortly after renaming the team the Ethiopian Clowns.

In a "tip of the cap" to the 100th anniversary of the Negro Leagues, the Miami Marlins donned throwback Miami Giants uniforms yesterday when they took the field against the Atlanta Braves. The team partnered with Florida Memorial University, South Florida's only historically Black college, to program the day's events. The school's choir performed "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing," a song now known as the "Negro National Anthem," before the game.

It wasn't just Black ballplayers who were marginalized before integration. Latino ballplayers were also relegated to play separately, and Miami was the place where teams from the Caribbean faced off against their Negro Leagues counterparts. Buck O'Neil recalled a Cuban pitcher nicknamed "Cocaína" García, who "got his name from his wicked curveball, which made all us hitters go numb."

And if South Florida was a hub, its center was in Overtown.

Overtown boomed back then. O'Neil recalled the vibrancy of the place, reminiscing about living only a short distance away from his home ballpark. "For the first time in my life," he wrote, "I actually got a salary for playing baseball: ten dollars a week, plus room and board. We stayed in a hotel over a theater on Second Avenue, and I could look down onto the street and see the sidewalks crowded with black folks."

O'Neil recounted staying at the Sir John Calvert Hotel. The hotel, located at 276 NW Sixth St., was a popular hangout. Etta James performed there. Where it once stood, there's now an empty lot next to the highway.

While there, O'Neil went on a hunting and fishing trip to the Everglades with the inimitable pitcher Satchel Paige. O'Neil thought to kill some water moccasins for a kick, but Paige stopped him.

"If the snakes were hanging around the John Calvert Hotel," Paige said, "sure it'd be OK to kill 'em. But this is their domain. We're the intruders."

Paige came back to South Florida later in his career, in the '50s, to play for a then-minor league team, the Miami Marlins. According to a biography by University of Miami history professor Donald Spivey, Paige and his wife, Lahoma, settled into a still-segregated Miami and became a "part of the after-hours cultural milieu of Overtown." The two were regulars at the Sir John, spending their nights dancing or sipping cocktails alongside Black entertainers like Sammy Davis Jr. and Sarah Vaughan. (The Paige roots are strong in Miami: The Marlins honored his legacy at yesterday's game, charging his son Robert Paige with throwing out the first pitch.)

A tax card photo of Dorsey Park, circa the 1930s

Photo courtesy of University of Miami's Office of Civic and Community Engagement

"Miami's city commission designated most of Overtown as 'industrial' in the 1920s to circumvent a Supreme Court ruling that declared racial zoning to be unconstitutional," says Jorge Damian de la Paz, a senior program manager at UM's Office of Civic and Community Engagement. "This zoning change allowed the city to restrict residential construction in the neighborhood and effectively maintain the color line without using overt racial language."

Despite the conditions, Overtown maintained its vibrancy. Some Negro Leagues games at Dorsey Park felt like barnstorming events, but others attracted crowds in the thousands. (Newspaper clippings show, there was a reserved "whites only" section of the grandstand.)

Many called Overtown the "Harlem of the South." It wasn't just the glory of the neighborhood, but also radical self-expression that connected the two places.

That connection leaked into the sports world, too. Harlem had its Globetrotters, a basketball team of skilled entertainers and showboaters whose performance was so beloved that they still perform to this day. Down here in Miami, we had their baseball surrogates, the Ethiopian Clowns.

The Clowns evolved from the Miami Giants in 1937 when the Negro Leagues scrambled to adapt to the looming integration with other forms of entertainment. It was in Dorsey Park that the Clowns are purported to have invented shadowball, a mimetic game of ball-less baseball. (Imagine the "hidden ball trick," but the ball never shows up.)

Teams like the Ethiopian Clowns turned the historically racist minstrel show on its head. Players took stage names like Haile Selassie, Tarzan, and Abbadabba, and donned grass skirts. Some players, like O'Neil, found the performances to be offensive and demeaning, while others saw them as a politically subversive act, an opportunity to call attention to the stereotypes imposed on the ballplayers by their oppressors. The Clowns played full games at Dorsey Park entirely in whiteface.

Murals of Black ballplayers line the wall outside of Dorsey Park today. The most recognizable is a reproduction of an illustration of catcher Josh Gibson. The original image was designed by the world-renowned artist Kadir Nelson for his book We Are the Ship: The Story of Negro League Baseball.

In the book, Nelson wrote of Gibson: "Josh hit everything: fastballs, curveballs. Couldn't fool him. Pitchers would just have to pitch and pray. He was so good, people started calling him 'Mr. Black Baseball.' Some even called him the 'Black Babe Ruth,' but others say that Babe should have been called the 'White Josh Gibson.'"

Gibson hit 84 home runs in one season, and more than 800 during his career. Both of those numbers would top the record books, if they were officially accepted.

Gibson is one of many ballplayers painted on the walls of Dorsey Park as part of an ongoing mural project organized by Nelson's mother, Emily Gunter. She's the development director for Urgent, Inc., an Overtown-based community development organization that provides after-school and summer programs for kids. When I spoke with Gunter over the phone this summer, she was corralling kids into Zoom breakout rooms so she could make time to talk about a project that has been a great source of passion for her.

"It's 6,500 square feet of murals worked on by 300 local artists with the help of 3,000 individuals from the community," Gunter said. "Anybody that walked by while we were painting – from the homeless community to high school kids – would pick up a brush. We educated the kids about each one of the ballplayers we painted."

Gunter began working full time with Urgent, Inc. in 2007, shortly after making the move to Miami from San Diego so she could be closer to her daughter. She settled into a place at NW Tenth Street and NW First Avenue, just seven blocks from the dilapidated Dorsey Park.

"When I moved down to Miami, Dorsey Park was a dust bowl," Gunter said.

Practically speaking, the dust could have been traced to different sources: The construction materials for an ever-encroaching wall of highrises and their newly minted monikers – Wynwood, Edgewater, the A&E District – have been exported from Overtown plants for decades. But figuratively, the dust that Gunter observed lingering in the air of Dorsey Park could have been the ghosts of the ballplayers who used to draw crowds in the thousands there, holding the line in their particulate forms until they were given the memorial they deserved.

Gunter's mural project is ongoing. She hopes someday the city will help her construct a statue of Jackie Robinson at Dorsey Park, which is mostly quiet today. An occasional car speeds by, using Overtown as the back door between downtown and Wynwood. Inevitably, the paths of gentrification lead toward it from all directions, but this is nothing new. The neighborhood's been under siege for over a century.

There's a certain elusive aspect to the park. It hasn't been kept in the best of conditions over the years. As such, it remains one of the few remaining untouched vectors of history in the urban core of the city. It's a sort of energy vortex whose qualities are most palpable at the crepuscular hours. At sunrise, the highrises to its east cast shadows over Dorsey Park and at sundown the lights switch on, revealing dust to the night sky.