David Winker, a business attorney involved in the effort to recall Miami City Commissioner Joe Carollo, was the subject of a 96-page political dossier that an unknown party sent to city officials in late July. The lengthy document includes screenshots of Winker's social-media posts, accusations of code violations, and insults about his weight. It also includes sensitive personal information, including Winker's date of birth, address, and driver's license number.

The pages of the document that include Winker's driving history and traffic record suggest that someone impersonated Winker by using his Social Security number. A section of the page from the Department of Motor Vehicles website states, "Your Social Security number has been verified. Thank you," and shows some of Winker's past traffic penalties.

For that reason, Winker believes whoever created the dossier may have violated Florida's Driver Privacy Protection Act, which protects a person's personal information from being accessed through their driving record.

Winker says he feels he could now easily be the subject of identity theft, and he plans to sue "John Doe" for the violation. Through the lawsuit, he should be able to subpoena the IP address of whoever logged into his driving record and find out who put the dossier together.

Because the dossier was shared among city employees, Winker also intends to sue the City of Miami so he can find out who sent the dossier. Winker believes the dossier was politically motivated and came from a city employee who holds a grudge against him.

Beyond representing the group calling for a recall of Carollo in a case against the city, Winker has openly criticized City Attorney Victoria Mendez for defending Carollo in the recall effort and acting as his "private law firm." He also has filed ethics complaints against the MLS soccer stadium construction effort.

The dossier includes 20 pages of Winker's tweets and various social-media posts about Carollo and Mendez, calling them "assaults." The author of the dossier claims to be a "concerned citizen" who lives in Winker's neighborhood, but Winker thinks it may be someone connected to the commissioner and city attorney.

"To me, clearly it's retaliation," he says. "I've pissed people off at the city."

Shortly after the document was sent to city officials, Winker found a notice of code violations tacked to his door, stating that his house had been inspected. He was cited for unpermitted additions to the property and for allegedly operating a business out of his home without a license. The notice said he could be subject to arrest unless he paid a fine and rectified the alleged violations.

Winker and his wife, Cristina Hernandez, tell New Times they were both in the house the entire day before the notice was posted and that no one came in to inspect. An NBC 6 report found that the investigative work was done online but not in person.

A city spokesperson tells New Times via email that code violation-cases are driven by complaints and inspected on a case-by-case basis. Because code-compliance employees can't enter a home without a warrant, they sometimes use other tools to investigate claims of impropriety.

"Observation of unusual activity outside of a residence, such as consistent in-and-out visitors regardless of day or time; observation of transactions taking place in front of a residence between occupants and visitors; statements from neighbors; reviews of publicly available business license documents; and interviews with customers" are some of the methods investigators use to check for code violations.

Winker says he called the number listed for the code inspector to ask him to return to the home, but no one answered. New Times called the number various times and left a voicemail but did not receive a response.

The notice cites Winker for allegedly running a law firm out of his home without a business license, which would violate city codes. A similar violation occurred in 2010 when then-Miami Commissioner Marc Sarnoff was caught running a law practice out of his home without permits.

Winker, however, argues that his home has no dedicated space for a law firm, saying that he handles his clients online or meets with them at their homes or online. He also pays a county business tax.

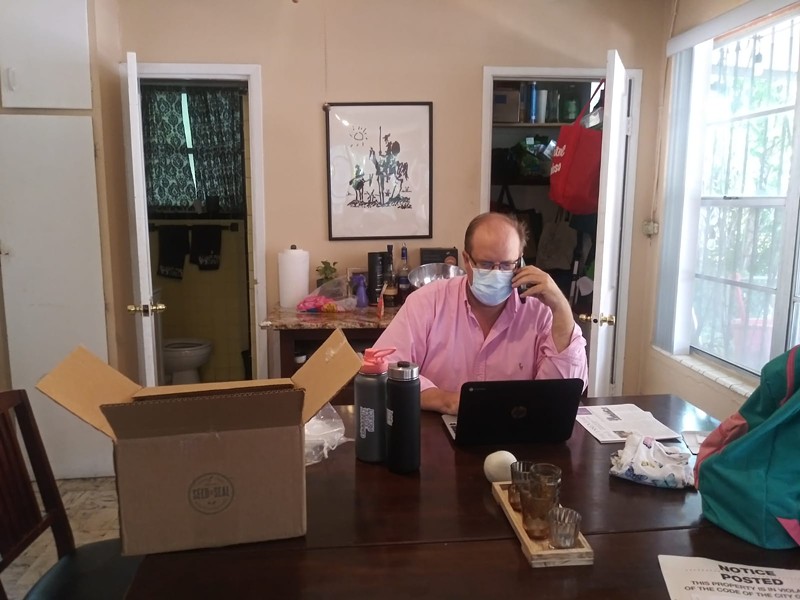

"I don't have a dedicated space. I work on the kitchen table," Winker says.

New Times visited Winker's home, which is listed as the address of his law firm on the Florida Bar website and Sunbiz, a database of Florida corporations. The attorney's workspaces include a dining-room table where his child's toys and laundry share space with his laptop, and a computer desk inside a storage room that contains family books and other belongings.

The case against Winker would seem to call into question the entire nature of working from home, as many people find themselves doing work from dining-room tables and bedrooms while the pandemic keeps them away from shared spaces.

"This is the intersection of the way we're doing business now and these zoning codes. More people are gonna be working from home — how do you regulate that?" Winker asks.

In a statement to Channel 10, Mendez said that as long as residents have a legal workplace away from home with proper licenses and are working remotely temporarily, they won't be cited.

Mendez herself fell under scrutiny last week in a situation similar to Winker's. Billy Corben, a local documentarian and political activist, criticized her because she has four businesses registered to her home address, including a personal law firm under her name.

New Times confirmed that Mendez's law firm is registered to her home address without any business licenses. And she isn't the only one. Deputy City Attorney Barnaby L. Min also has his home address listed as the principal location for his law firm, Barnaby L. Min, P.A.#BREAKING: Miami city attorney @VickyMendezEsq falsely cited a critic for practicing law from home during a pandemic, threatening him with arrest, but she and her husband have FOUR private companies registered to their house with NO home office permits #BecauseMiami pic.twitter.com/cJQBAqtdjU

— Billy Corben (@BillyCorben) August 12, 2020

Mendez tells New Times via email that she does not use her personal law firm because she has always worked as a municipal attorney, and that therefore she is exempt from the rule.

"I am not running a law practice out of my home. I opened the PA in 2007 to hold my name in case I ever went to the private sector. I never did. That PA has never conducted business. It does not require any type of licenses," Mendez says.

She goes on to say that the other businesses are her husband's and that they comply with state laws. Although Mendez is listed as a registered agent for something called the Abuelos Foundation on Sunbiz, she says the organization was started by her sons and is exempt from home licensing rules.

"Mr. Winker seems to think by bullying me on social media I will stop defending the city," Mendez says. "Instead of attacking Hispanic women lawyers, he should focus on solving his code issues, legalizing his home office, and get[ting] his house in order, so that he can properly assist his own clients."

In a letter to sent to Mendez and the city administration on Sunday, Winker refuted the code violations by stating he has no dedicated space for his business in his home, that there was no inspection, and that the city code appears to say that anyone working at home during the pandemic needs a business license.

"I am working on a laptop at a kitchen table. Is that 'operating a profession?' If so, it would appear that thousands of Miami residents are in violation and subject to arrest," Winker wrote.

Winker says he plans to battle the violation claims while also suing the city over the privacy breach.

"Someone is weaponizing the tools of government," he says. "Do we really want the government making dossiers on public residents?"