They clamber out of the vehicle and into the tangle of tall grass and poisonwood to find their quarry trapped in a cage just outside Everglades National Park. It's a tegu, a lizard native to South America that has been attacking the Everglades in droves and competing with the Burmese python in the hell-for-leather race for the title of South Florida's Most Dangerous Invasive Reptile.

Tegus came to Florida through the exotic pet trade, and though they can make good pets for attentive owners, many are abandoned after growing to their full size (about four feet long from nose to tail) and left to fend for themselves on Florida's wildlife.

What makes the reptile particularly dangerous is its diet.

"With tegus, the big concern is what they're eating. They'll eat anything from plants to animals to the eggs of anything that lays them, including alligators," says Kevin Donmoyer, invasive-species biologist with Everglades National Park.

The prospect of tegus spreading throughout the Everglades and munching on native species' eggs before they hatch is a major threat to the local ecosystem. After the first adult tegus were captured in Everglades National Park in 2017, their population in South Florida has been on a steep rise. In 2020, hunters captured 961 of the big lizards in and around the park; in 2021, 844 were captured.

That looming threat is exactly why Everglades National Park created a tegu trapping program wherein park staff, alongside graduate researchers with the BioCorps Internship Program, go out into the park and along the perimeter to trap, retrieve, and study the critters before they can ravage the local ecosystem.

Joshua Mayo is a BioCorps intern and part of the tegu trapping team with Everglades National Park. The internship is paid for by the University of Florida with funding from the Alliance for Florida's National Parks, a nonprofit that raises money to help the state's national parks pay for programs.

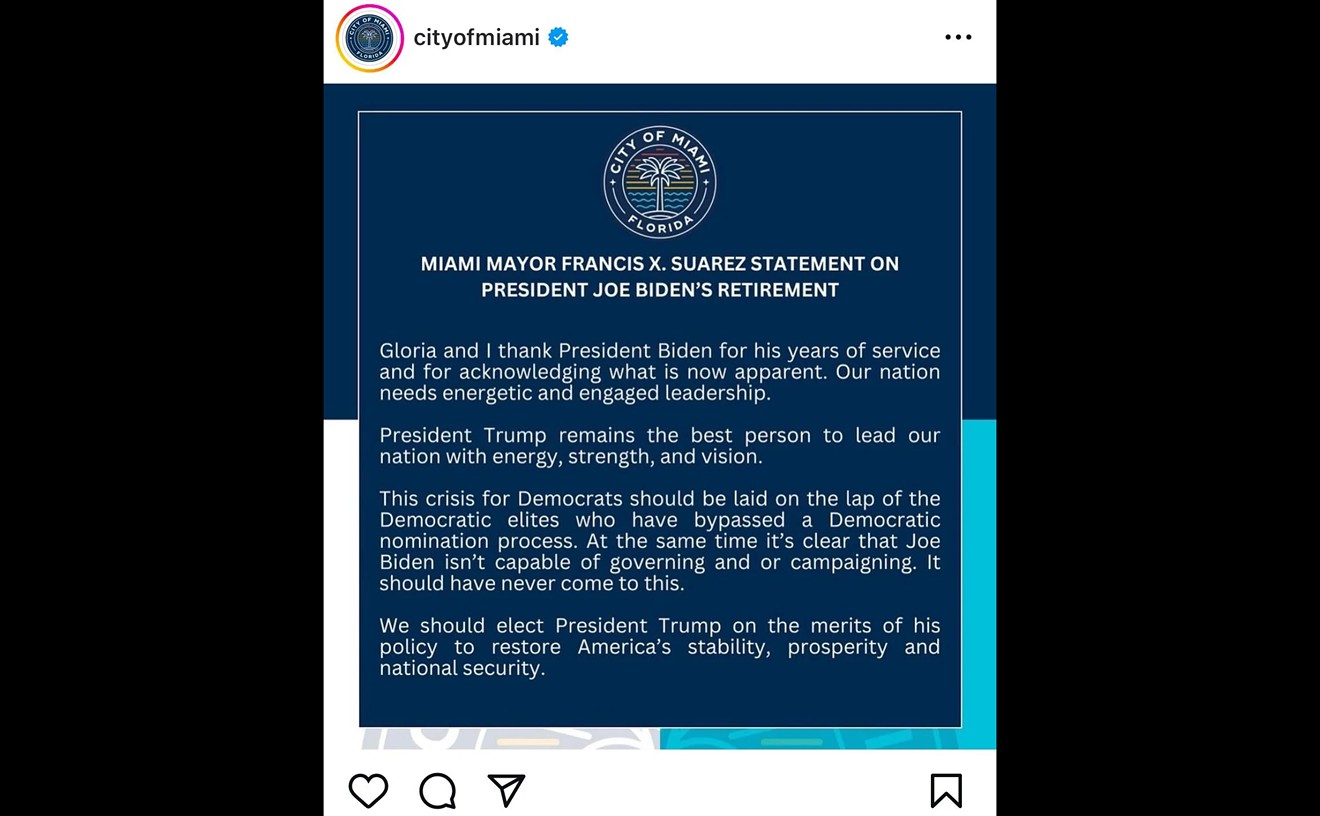

Joshua Mayo, a BioCorps intern with Everglades National Park, bagging a captured tegu for research and removal.

Photo by Joshua Ceballos

Equipped with a GPS loaded with the locations of each trap, the researchers drive government trucks to each one to see what might have wandered in. Lately, Donmoyer says, they've been contending with thieves stealing tegu traps, so he and Mayo are on the lookout for missing cages as well.

When a tegu is found, a researcher gently places it in a linen bag that looks a lot like a pillowcase, double bags it, and then places it in a locked box in the bed of the truck.

After three hours of driving through the wilderness searching for lizards, the researchers return to the lab at the Daniel Beard Research Center to record data on their haul.

On this day, Donmoyer and Mayo bag three tegus, one of which measures nearly two-and-a-half feet long. The scientists log their length, weight, and sex before caging them individually to await handoff to U.S. Geological Survey personnel, who will euthanize them with a bolt gun.

Donmoyer explains that the work must be done in order to protect native species. "All of us like them and we treat them with tremendous respect," he says. "If their impacts on the Everglades were negligible, we wouldn't be doing this.""We treat them with tremendous respect. If their impacts on the Everglades were negligible, we wouldn't be doing this."

tweet this

Mayo, who came to Florida from California for the BioCorps internship because of his love for Florida wildlife, treats the animals with care even while collecting data.

"I actually love them, I think they're such cool animals," Mayo tells New Times.

By capturing tegus, researchers not only work to curb the population of invaders, but also contribute useful data that scientists can use to learn how tegus behave in Florida and how best to deal with them, as knowledge about their behavior here is still limited.

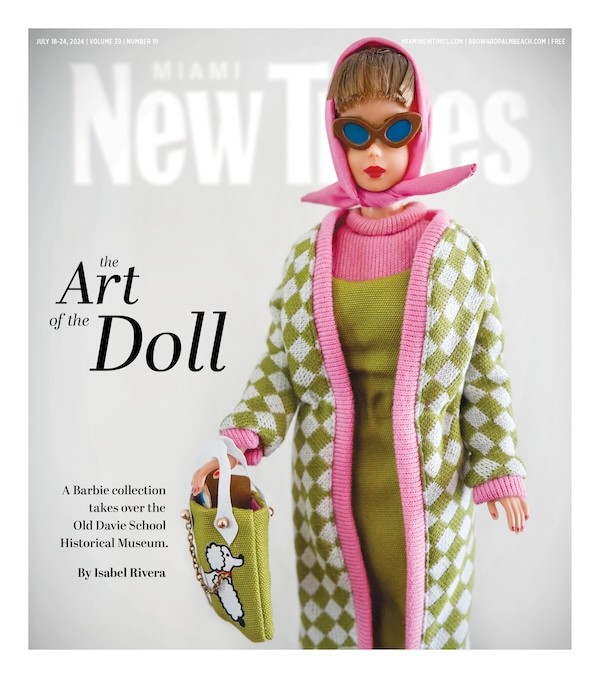

An adult male tegu measuring nearly two-and-a-half feet long. Full-grown tegus can reach four feet, but they needn't be that big to consume the unhatched eggs of native wildlife.

Photo by Joshua Ceballos

"We don't have accurate population estimates for tegus, so we just report the data without making assumptions about how much we're cutting down the population," he explains.

Still, whatever dent they can make is a step toward preserving the Everglades ecosystem, which is already under fire from many directions.

"The Everglades are already facing so many threats," Donmoyer says. "Invasive plants, human behavior, pythons — having the tegus as one more thing could be a tipping point."