Update published 9:35 a.m. 9/29/2022: Lee County Sheriff Carmine Marceno released a statement claiming that inmates at the downtown Fort Myers jail are safe. He says that "in an abundance of caution, inmates were relocated within the main jail to a higher floor."

More than two million Floridians were told to evacuate as Hurricane Ian approached Florida's southwest coast. When the storm came ashore on September 28, it decimated neighborhoods with Category 4 winds and brought a destructive storm surge that submerged city blocks in Lee County.

But while mandatory evacuation orders had been in place across the county for more than two days, sending scores of residents fleeing inland across the state, one group remained in the storm's direct path with no option to leave.

According to Lee County Sheriff's Office spokesperson Anita Iriarte, the sheriff's office declined to evacuate inmates from its 457-bed downtown Fort Myers jail as Hurricane Ian neared Category 5 status and closed in on the area.

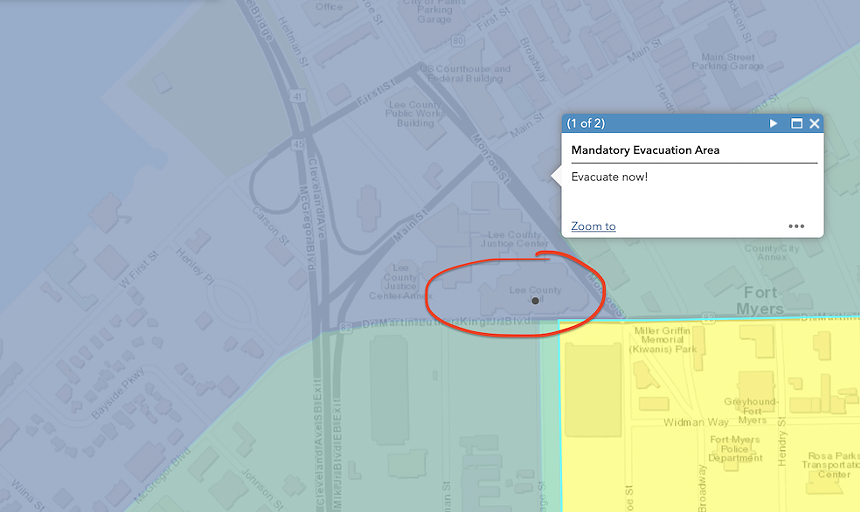

Lee County's own map indicates that the jail is in a mandatory evacuation zone. In advance of the storm's arrival, the National Hurricane Center's forecast suggested that downtown Fort Myers would face the threat of a storm surge of 9 feet or more.

"In the event of an emergency, we have procedures in place," Iriarte tells New Times in an email. Around 1 p.m. on September 28, when scenes of destruction were unfolding across Lee County, the sheriff's office maintained that the "inmates are safe."

The Fort Myers downtown jail is located less than five blocks from the Caloosahatchee River, in a district prone to flooding from storm surge.

Screenshot via Lee County

Footage of Edison Bank in Fort Myers, roughly two blocks from the river and about a half-mile away from the jail, showed a downtown block inundated with flood waters around 3:45 p.m. The water in one neighborhood in the downtown district reportedly rose to four-feet deep by 4:30 p.m.

A county map shows the jail in evacuation zone A, which includes areas most vulnerable to storm-surge damage. The jail is situated on the map on the edge of lower-level evacuation zones B and C.

Notably, most people in processing jails like the downtown jail in Lee County have yet to be convicted of the alleged crimes for which they were detained. Some have been arrested and can make bail within hours or days, while many others can't afford to pay bail and wind up behind bars until their trial date. According to Prison Policy Initiative, only a small number have been convicted, and of that subset of inmates, many are serving misdemeanor sentences under a year.

The Lee County Sheriff's Office Corrections Bureau manages three main facilities — the downtown jail, a core facility, and a community program unit (CPU), according to the department's website. The downtown jail is a maximum security facility with 457 beds that serves as the intake and booking center for arrestees in Lee County; the core facility is a medium/maximum jail with 1,216 beds that serves as a primary housing facility for inmates; and the CPU is a minimum security facility with 336 beds that offers programs for alcohol and drug treatment and societal re-entry skills.

The sheriff's office had an average daily inmate population of 1,712 in 2019. Iriarte declined to provide the latest numbers, citing the state of emergency brought about by Hurricane Ian.

This wouldn't be the first time incarcerated people were left behind during a major hurricane.

In 2018, during Hurricane Florence, prison officials and sheriffs left thousands of prisoners, guards, and staff behind in evacuation zones at a state prison in South Carolina and three city jails in Virginia, Mother Jones reported.

In 2017, during and after Hurricane Harvey hammered the Gulf states, thousands of people in Texas prisons were reportedly left to suffer in poor conditions in storm-wrecked facilities. While several prisons were evacuated, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) declined to evacuate more than 8,000 prisoners across four facilities –– leaving them in cells that wound up being flooded with urine and feces-contaminated water, and without the ability to shower, flush toilets, or change clothes for two weeks, according to The Nation.

In 2005, as Hurricane Katrina slammed New Orleans, a sheriff's department purportedly abandoned hundreds of inmates imprisoned in a city jail.

The Florida Department of Corrections (FDC) announced on September 28 that it had evacuated 2,500 inmates or detainees from 23 state facilities, stretching from Miami to Jacksonville.

"Multiple satellite facilities, community work release centers and work camps were evacuated in an abundance of caution. Inmates were relocated to large main units (parent facilities) better equipped to weather the storm," FDC said.