But today, a large-scale development backed by one of Massó's descendants threatens to destroy a potential bat habitat in Miami-Dade County, pitting a Bacardí heir against an animal that's long been intertwined with the family brand.

After the Calusa Country Club closed down in 2011, the golf course near West Kendall became a fertile green space full of wildlife. Nearby homeowners, who have for years fought against the property's development, want to keep it that way. But the landowners of the club — a joint venture that includes a company owned by Facundo L. Bacardí, chairman of the board of Bacardí Limited — want to turn the property into a gated residential community.

Bacardí and the real estate development company GL Homes won the right to build houses on the property late last year, when county commissioners voted to release them from a covenant that required the land to remain a golf course until 2067.

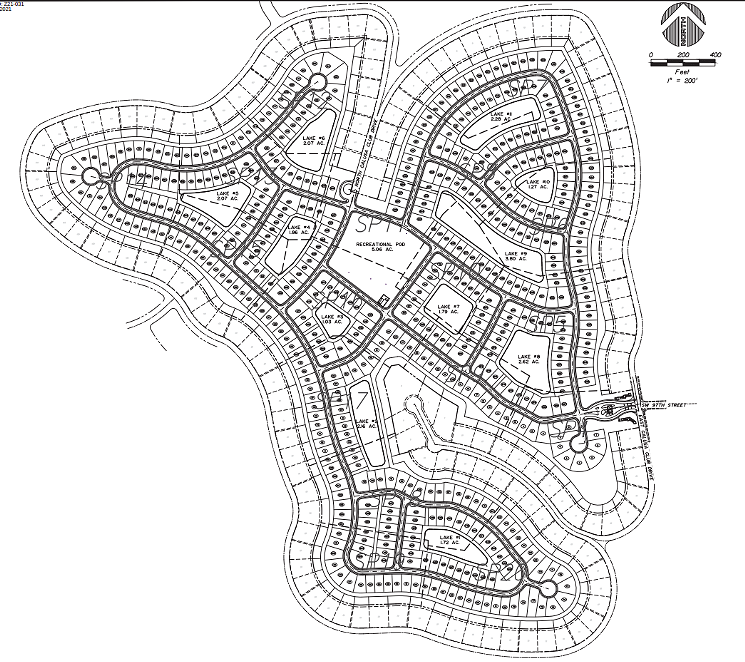

The land is currently zoned to allow for 33 homes, but the developers want to build many more. They've petitioned the county to rezone the golf course to allow for 550 single-family homes, with the aim of creating a snug gated community in the middle of the existing Calusa neighborhood.

Some homeowners who live around the golf course remain in opposition to the project, preferring the land remain as it is today — a 168-acre green space and habitat for all manner of animals.

"Even though [the country club] closed, it's still a beautiful, picturesque view. We constantly see all kinds of birds. We see foxes at night, and there are bats. You almost feel like you're in the middle of a safari in Africa, but you're in the middle of Kendall," says Vanessa Vazquez, who has lived in Calusa since 2016 and whose backyard faces the golf course.

The lakes and trees of the former Calusa Country Club currently serve as habitats for all manner of wildlife, which residents fear will be displaced by development.

Photo by Dennis and Victoria Horn of Save Calusa Neighbors

The conservation group agreed, and earlier this year, it set up sonar-detecting equipment in the backyards of a few homeowners who live adjacent to the golf course.

The nonprofit found evidence of one of the nation's most endangered bat species, the Florida bonneted bat.

Over the course of 42 nights from February to March, Bat Conservation International heard an average of 287 calls from the bonneted bat each night. Melquisedec Gamba-Rios, a research fellow with the organization, tells New Times that based on specific calls that were detected, it's clear that endangered bats are flying over the golf course and foraging for food on the property.

Because the bat conservationists couldn't enter the golf course, which is privately owned, they couldn't determine if the bats were roosting, or sleeping, on the course. If bats are found to be found roosting in a tree in the development area, Gamba-Rios says the roosting area would be protected by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Florida bonneted bats are a federally endangered species only found in South Florida. They don't reproduce often, and they prefer to forage over open spaces, making golf courses somewhat ideal destinations. Development and urbanization have wiped out many of their natural habitats.

"The Florida bonneted bat has a small range distribution" — meaning it can thrive in very few places, says Gamba-Rios. "That means that any threat or activity that disturbs their environment has a higher impact."

Bat Conservation International wrote a letter recommending that a formal acoustic survey be undertaken on the golf course to determine whether endangered bats are using the land to roost. Supporters of Save Calusa Neighbors sent the letter to Miami-Dade's Department of Regulatory and Economic Resources (RER) on March 30, asking that the project be put on hold until the developer performs a formal wildlife survey with approval from the county.

The county's Department of Environmental Resources Management (DERM), which falls under RER, had already recommended in a March 12 memo that the county undertake an environmental survey, advising that the property might be a habitat for endangered species like the bonneted bat and the Florida burrowing owl.

Facundo L. Bacardí and his fellow landowners have yet to respond to those wildlife considerations. The property owners still have not contacted DERM to submit any environmental or acoustic survey for the property, according to a county spokesperson.

A representative for the landowners, Brian Adler, did not respond to emails from New Times or multiple messages left at his office seeking comment last week. Richard Norwalk, chief operating officer for GL Homes, did not respond to an email seeking comment last week.

The bat saga is only the latest effort by homeowners to stall the housing project.

A company owned by Facundo L. Bacardí bought Calusa Country Club in 2003 and closed the business in 2011, asserting that the club had not been profitable for years. When South Florida was battered by the likes of Hurricanes Wilma and Katrina in 2005, the club sustained damage that Bacardí did not repair, according to the Miami Herald. Since then, the land has lain fallow.

A written covenant previously held that the country-club land was to remain a golf course for 99 years, or until 2067, unless otherwise determined by the board of county commissioners, with the consent of 75 percent of homeowners whose backyards abut the golf course.

After the club closed in 2011, Bacardí offered those homeowners a $50,000 settlement to sign a covenant waiver but failed to garner sufficient support. He then sued residents to release the covenant, leading to a prolonged legal battle — one that many expected to end in 2016 when Florida's Third District Court of Appeals upheld the 99-year covenant.

But after the court decision, the golf-course owners negotiated a new settlement with the surrounding homeowners to induce them to sign the waiver, including a stipulation that furnished them with an increase in backyard space. The waivers were signed by 120 out of the 146 surrounding homeowners, comfortably exceeding the required 75 percent, and then presented to the county commission.

The exact details of the deal are not public, and homeowners were made to sign nondisclosure agreements before being offered the terms. But Amanda Prieto, a leader of Save Calusa Neighbors who lives across from the golf course, says she's heard that some homeowners were offered up to $300,000 to sign. The households that did not sign the waiver did not receive any payment.

The company's site plans for the rezoned area now include 50 feet of buffer space between the backyards of the existing homes that surround the golf course and the homes that will be built in the new development.

Current site plans for a rezoned Calusa golf course near West Kendall, which includes 550 single-family homes and two entrances.

Photo via Miami-Dade County Department of Regulatory and Economic Resources

Ever since the deal was struck, the once close-knit Calusa community has dealt with discord and feuds between homeowners who signed the waiver and support the development and those who don't.

"When I speak out against the development, I get harassed. Neighbors either stop talking to you completely or harass you," says Vazquez, who did not sign the waiver. "It's been horrible for the community. It's broken a lot of community spirit and camaraderie."

In a recent online petition that tallied more than 1,100 signatures, supporters of Save Calusa Neighbors say they're concerned about the infrastructure and traffic impact the housing development will have on an already traffic-choked area.

Vazquez says her mother has worked as the after-school director for Calusa Elementary School, near the golf course, since Vazquez was a child. She remembers parents running hours late to pick up their children because traffic near Kendall was terrible even back then. She fears the repercussions of building 550 additional homes and potentially adding twice as many cars to the roads.

"We have school traffic, work traffic, we have traffic from people cutting through our neighborhood, and there's no good public transportation," says Vazquez. "Now add 1,000 more cars. I can't imagine what it will look like with all these homes."

Residents like Vazquez and Prieto feel their concerns about the development are going unheard by the developers and Miami-Dade government. They say that since the covenant was released, there has been no community outreach to homeowners slightly farther from the edge of the golf course who will be affected by the traffic influx.

Although Bacardí and the developers have the right to develop on the property, some residents hope they can be persuaded to reconsider their plans.

"In my optimistic, utopian dream, it would stay exactly as it is. The county would reimburse Bacardí and make this a park," Vazquez says.

Prieto says she and other homeowners moved to the area because of the country club and want to continue to enjoy the lifestyle of a golf-course community.

"We would love for it to be a golf course, but a park would come in a close second," Prieto says. "We all moved here because we thought it would be a golf course forever. We want to let wildlife be in their habitat."