Built atop an old golf course, a polished new Miami community was marketed as a "rare gem" with "pristine lakes and natural preserves." Taking advantage of low real-estate prices in the wake of the 2008 collapse of the U.S. housing market, buyers gobbled up units.

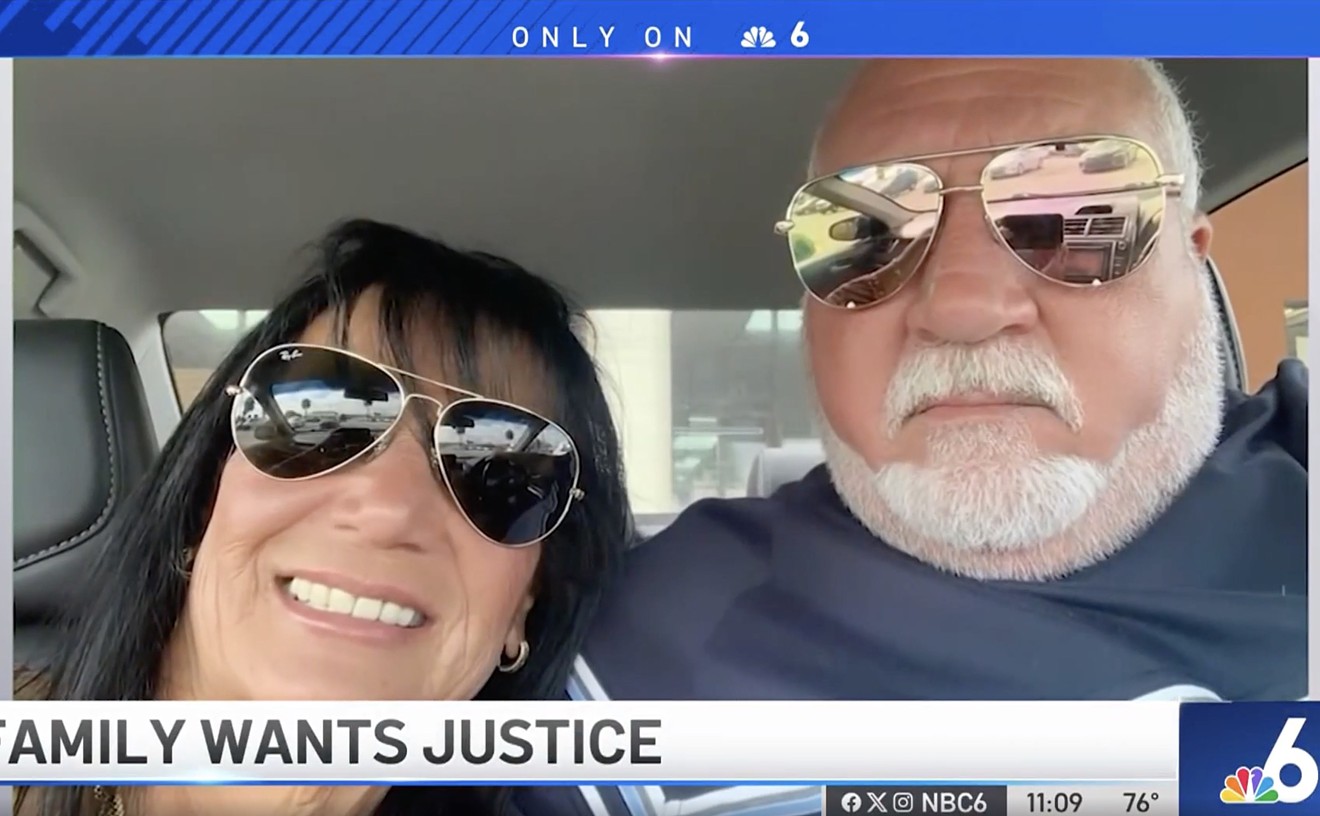

Ten homeowners in Aventura Isles now allege the sleek ads and slick sales agents were a façade that covered up the site's history of chemical contamination. Their season's greeting was a lawsuit accusing the developers of hiding the contamination in an effort to bolster sales.

The plaintiffs claim that when they bought properties in Aventura Isles, the developers and sales agents never disclosed that there was an ongoing soil cleanup project and that Miami-Dade County had placed usage restrictions on the site owing to elevated levels of arsenic and the pesticide dieldrin.

Allegedly, more than $160 million worth of homes in Aventura Isles were sold off before the developers admitted to the county that the land-use restrictions had never been recorded in public records as mandated.

Defendants in the case include Williams Island Ventures, Encore Home Builders, and a slew of related entities with shared corporate leadership.

Gene Stearns, attorney for Encore, denies the developers concealed contamination. "The lawsuit is headed nowhere," he says.

Stearns characterizes the complaint as a money grab. "They're making an argument hoping someone's gonna pay them. Well, that's not gonna happen," he says. "The developers did everything they should have done to make the community safe."

If the story sounds familiar, mark it as another chapter in the fallout from short-sighted overuse of herbicides and pesticides on South Florida farmlands and golf courses of decades past. The issue tends to come to a head when developers acquire land for redevelopment and site testing reveals contamination.

The two contaminants in focus at the Aventura site are serial offenders in the state's chronicle of endemic contamination. Dieldrin, a neurotoxic insecticide banned by the EPA in the late 1980s, is notorious for persisting in the environment. Arsenic, a potent carcinogen long used in herbicide and pesticide products, doesn't break down and can hang around in soil indefinitely.

By all accounts, the contaminants were tainting the land long before the developers acquired it. Aventura Isles' soil woes arose from compounds applied from the 1960s until 2003, while the property was the site of the Williams Island Country Club's golf course. Another source of the contamination might have been prior use of the land for crop farming.

The lawsuit claims that after acquiring the site, the developers chose a low-cost remediation option that involved blending contaminated soil with ostensibly cleaner soil and then redistributing it around the property. Hauling all of the contaminated soil away would have been more expensive, with an estimated cost of $20 million, according to court documents.

The strategy was meant to dilute the contamination. In actuality, the plaintiffs allege, it spread the contamination to residents' yards.

Remediation teams did remove more than 20 "hot spots" of tainted soil and take it offsite, court documents show.

"None of the levels of chemicals and arsenic in this land cause any hazard to human health," Stearns tells New Times. "No real danger is alleged in the case. That's because it doesn't exist. The developers went through an extensive process of soil remediation, excavating, and sampling the site over and over again. Before the project ever began, county environmental officials had to sign off on it."

Defendant WI 825, a company held by real-estate investor Arthur Falcone, bought the sprawling tract in 2004 and later transferred it to Williams Island Ventures in 2010 in preparation for development, according to court filings. Falcone and his associates Anthony Avila and Neil Eisner are said to have spearheaded the buildout.

After the housing market began to recover from the 2008 collapse, the developers started the soil cleanup project and set construction in motion.

Despite the cleanup efforts, local regulations required that significant land restrictions be recorded in the community's property deeds. Groundwater was barred from use as a drinking-water source; no digging was permitted beyond 18 inches without informing environmental officials; undocumented removal of soil and groundwater from Aventura Isles was prohibited.

And sellers had to warn buyers about the contamination.

In 2016, the lawsuit alleges, developers admitted to the county that they never recorded the restrictions.

"As we know, the nature of the development and the environment cleanup typically require a covenant to be placed on all of the properties. Unfortunately due to errors that occurred, that is no longer feasible with respect to the individually owned properties," the developers allegedly wrote to the county environmental department via legal counsel in March 2016.

By that point, roughly 69 acres of the 148-acre property had been transferred to buyers.

The developers' then-attorneys sent county environmental officials copies of condo association documents that purportedly had disclosed the contamination to homebuyers in lieu of the legally required restrictive covenants. The officials responded, deeming the documents "inaccurate and insufficient to provide a level of protection equal to that of a covenant."

The lawsuit claims the purported condo association papers weren't included in sales packages presented to the plaintiffs.

"By failing to... disclose, defendants wrongfully deprived plaintiffs of the chance to make a meaningful choice for themselves and their families in the face of uncertain health and liability risk," the complaint states.

Purchased between 2013 and 2015, the plaintiffs' five Aventura Isles homes ranged in price from $208,000 to $418,000. The lawsuit does not present any personal injury claims, nor does it put forth evidence to suggest anyone was made sick by the contaminants.

According to Tom Robertson, an attorney who helped the developers through the regulatory process, soil cleanup at Aventura Isles was monitored closely by Miami-Dade County. The top two feet of soil around the community was blended with uncontaminated soil to safe levels, he says.

"When contamination is fairly low, blending soil makes sense. You end up with mixed material where the levels are well below being dangerous. There are plenty of residential communities where this same method has been used," Robertson says.

"There has been a lot of agriculture in the South Dade area since the 1930s," Robertson adds. "For years, Homestead and South Dade were the winter-vegetable capital of the country. Elevated herbicide levels are very common for residential neighborhoods once used for golf courses or agriculture."

Robertson clarifies he is not representing the developers in the litigation. He says Aventura Isles lots are "probably safer than [his] backyard," which is the site of an old mango grove.

Stearns, on behalf of Encore, maintains there was "full disclosure" of the soil issues "throughout the process of selling units" in Aventura Isles. He says aggressive local environmental regulations in the Miami area subjected the property to a lengthy period of regulatory scrutiny.

"If this land had been in any other county but Miami-Dade, we would not be talking about it," he contends. "Arsenic is everywhere. It's just a fact of life."

Groundwater monitoring over the past two years has shown that many of the surveillance wells at Aventura Isles register below the county's target cleanup levels for arsenic. But isolated spots still turn up high arsenic levels — in some instances more than 100 times the target cleanup levels. One of the latest remediation efforts involved plans to fence off some heavily contaminated soil on the property.

The developers' defense counsel claims that as long as the groundwater is not used for drinking, the elevated arsenic readings pose no imminent danger.

Earlier this year, county officials gave the developers a so-called variance to close the environmental-regulatory process on the property. The variance let the developers record revised community rules, which would include the land-use restrictions and provide a public record of the contamination issues.

Stoking the legal battle further, the plaintiffs take issue with a decision by the builders to turn over dozens of acres of undeveloped Aventura Isles land to the condo association. Stearns calls it a generous gift, bestowed on the association alongside cash to bankroll a conversion of the areas into recreation spots.

The plaintiffs say the "gift" was part of a plan to offload future soil cleanup responsibility onto the homeowners. The land is more of a liability than an asset, they claim.

Since 2004, when the former golf course was acquired, arsenic-based herbicides have been largely phased out of agricultural use in the United States. In 2009, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) canceled clearance for one of the last arsenic-based herbicides remaining in use in the States: monosodium methyl arsenate (MSMA). That compound was thereby banned from agriculture under federal regulations, though exceptions were made for sod farms, golf courses, and cotton farming.

In Florida, MSMA and other arsenic-laden compounds are no longer permitted as herbicides on golf courses, according to the EPA.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "19274298",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17482312",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482310",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482313",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]