An impish fellow wanders about, randomly grabbing men's butts while his friends giggle. Nearby stands a gentleman wearing no pants, only a chain-mail tunic fashioned from what appear to be the discarded pop tabs of 10,000 Pepsi cans.

Male strippers — about eight absolute beefcakes — sweat as they strut through the crowd, collecting dollar bills in thongs MacGyver'ed from nothing but dental floss and a dish towel. One does a twerking handstand in the corner, propping himself against a man who appears very content with his view: an overhead shot of the dancer's glistening buttocks, which, upon closer inspection, appear to have a glowstick nestled inside like a hot dog in a bun. It is gluteal coordination on a mind-blowing scale.

At any other concert, you might see an eyebrow or two rise in, at the very least, curiosity. But this particular fan base, which has gathered at Wynwood's Maps Backlot on a brutally humid May night, has been conditioned not to flinch at human sexuality. They are here to see an artist who showed them nearly 20 years ago that you don't have to sit back and listen to heterosexual men rhyme about what you should be doing with your body.

Her name is Katrina Taylor, and she showed the hip-hop world that defiance is not only possible but also damn fun. You probably know her better as Trina, and she's one of the most important female MCs ever, having paved the way for Rihanna, Nicki Minaj, and, yes, even Beyoncé.

"[Trina is] the best female rapper Miami ever had," says Ted Lucas, founder of the historic hip-hop label Slip-N-Slide Records. And though he might be just a tad biased, you won't find many Floridians willing to argue with that statement.

See, until Trina took the stage long ago, the boys had the microphone in Miami hip-hop. With it, they launched commands like missiles at the opposite sex: Sit down, shake that, suck this. And then Trina came along and went: OK, my turn. Now she's back, poised to drop The One, her first album in years, which she firmly asserts is her "best to date."

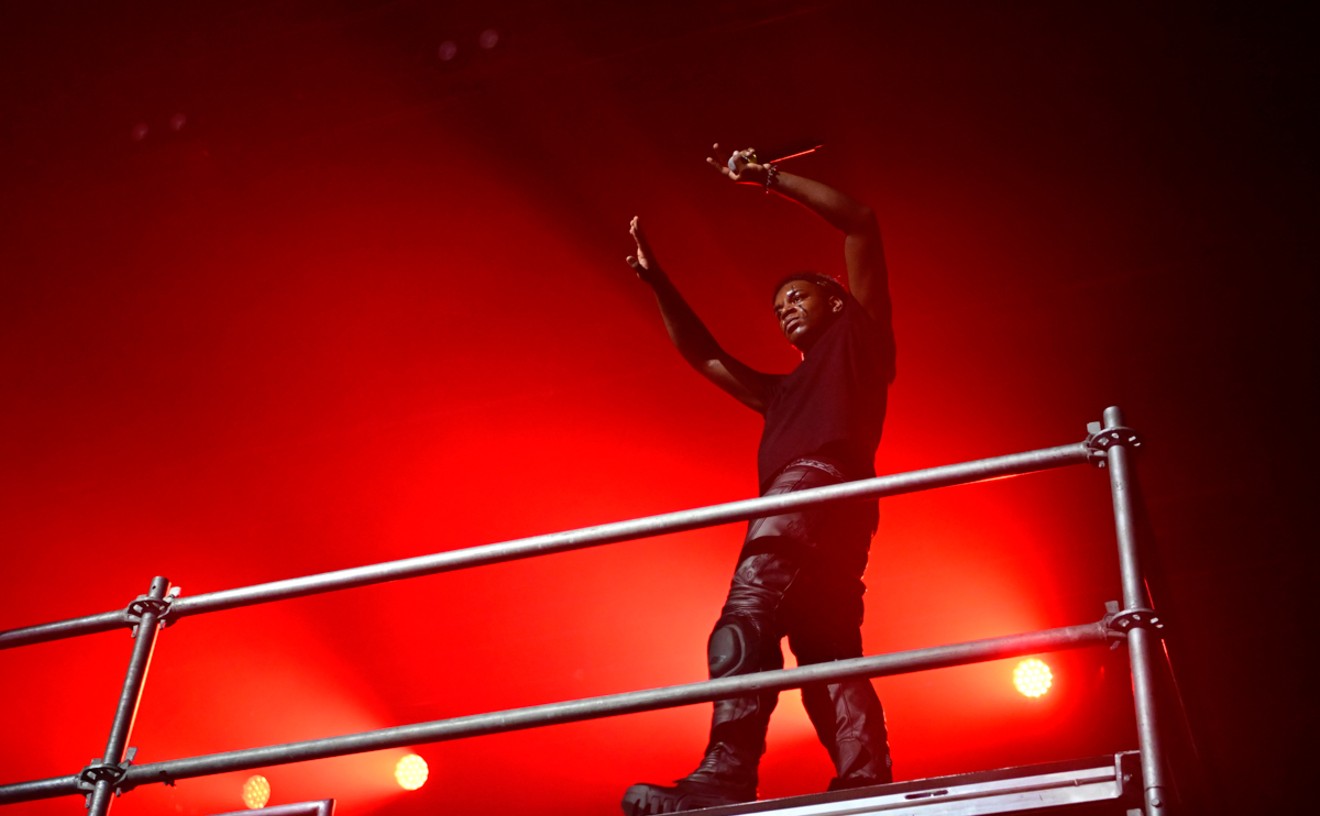

At 3:30 a.m., back in the Backlot, she finally struts onstage two and a half hours late, but her face shows no hint of disorder. She runs through a quick catalog of her most savage hits.

She opens with "Pull Over," a track from her debut album that is possibly the greatest booty-shaking anthem to emerge from Miami, a city that is to booty-shaking anthems what Wisconsin is to cheese. Next comes "Look Back at Me," a song that is best summed up by its current highest-rated YouTube comment: "You need a condom to listen to this!"

And right before she finally unleashes the fury of her biggest hit, "Nann Nigga," Trina pauses and scans her hometown crowd. "I dedicate this to everyone who supported me through my career and everybody who stuck with me to my sixth album," she tells them. "And to everybody who thought I couldn't do it," she smiles sweetly before flicking her middle finger in the air, "fuck you."

Most people, especially men, have always been afraid to approach Trina. The now-38-year-old gets it. The whole "baddest bitch" persona, lyrics threatening to "make him eat it while my period on" — these things can give a man pause.

When she began to notice all the nervous-looking boys standing in corners eying her like a zebra watches a lion, it made her laugh. "It's funny to me," she says. "I was like, 'These guys are so shaken up.'"

The ones brave enough to eventually say hello are always confronted with an unexpected reality. Trina is not scary unless you give her a reason. Her default setting is kindness. Today, perched on a stool outside an Italian restaurant in Brickell, she's generous with her attention, humbled by compliments, and doing her best not to let the server see how much she hates the margherita pizza growing cold in front of her.

If you grew up in Liberty City in the '80s and '90s, you probably knew Trina. And if you didn't, you definitely knew her mother, Vernesa, or — as you probably called her — Nesa.

One of five sisters born in the Bahamas, Nesa owned the local beauty salon, a small peach building that served as a community hub. Trina would get out of school, go straight to the salon, and listen. "Every day, you would see all these beautiful women getting glammed up," she remembers. They swapped stories and laughed. It was a positive and healing environment that offered respite from Liberty City's rougher edges. "Even though [Liberty City] can be grimy, the salon kept it glamorous for me," she says.

Her stepfather, another small-business owner, was also well known in the neighborhood. His nickname was Mr. Wonderful. "It was like I was popular before I was popular," Trina says.

She had no trouble making a name for herself. By the time she was a teenager, her reputation had traveled beyond Liberty City.

"She was always that chick that everybody knew about," says Corey Evans, a Carol City native. Though Evans would cross paths with Trina professionally a few years later (he'd eventually be her tour manager), back then he knew her only as "that popular chick that all the guys in Miami wanted to, you know, get with."

"Hollywood was a great guy, and he didn't deserve that."

tweet this

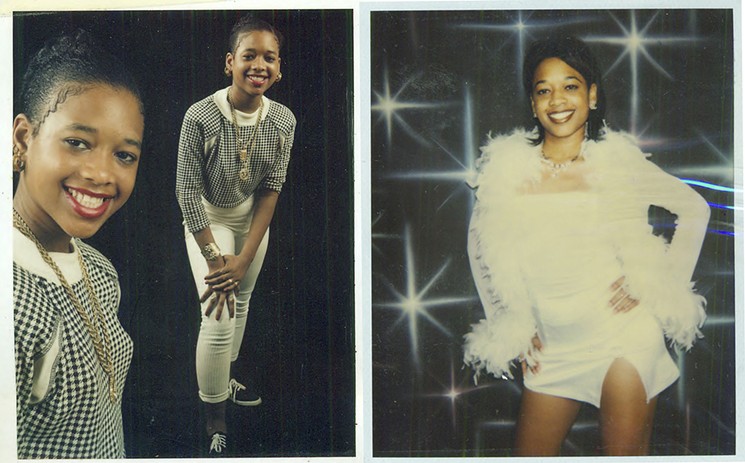

Trina was a celebrity among the 13-to-18-year-old Liberty City set. She was a majorette at Northwestern Senior High. She handily won the superlative of best dressed. And she and her crew were regulars at Uncle Luke's old spot, the Pac Jam, an alcohol-free teen club the 2 Live Crew frontman (and future New Times columnist) opened in the '80s.

Pac Jam was wild by any standards, but especially for kids barely out of middle school. There were no censored versions of anything, and the unfiltered raunch of early Miami bass was on full display — to 13-year-olds. Legend has it that, on more than one occasion, DJs stopped records to announce that someone's mom was outside to pick them up.

"I was the popular kid at the teen club," Trina admits. But she was certainly no pushover. She had buttons any reasonable person knew not to push, and her temper was well known. "She's definitely a sweet and loving person," Lucas says. "But we also knew, you better not get her wrong. If you get her wrong, that Liberty City, Northwestern bull gonna come out... She definitely fights then and will put her hands on you."

Needless to say, wooing Trina wasn't easy. But eventually, a young man named Derek Harris succeeded. Seven years her senior, Harris — better known to friends as Hollywood — was handsome, popular, and kind. He was a concert promoter who had ambition and connections. His half-brother, Maurice Young, would later become one of the most successful rappers to emerge from Miami: Trick Daddy.

"I actually introduced [Hollywood and Trina]," Trick says. He claims his brother offered $1,000 to get face-to-face with her. Trick never got paid, but Hollywood was Trina's first real boyfriend. They dated for about a year, according to Trina.

Then on June 22, 1994, Hollywood and a friend were gunned down while sitting in a Buick parked in Opa-locka. "He got in the car with the wrong person," says Trick, who was in jail at the time on charges of cocaine trafficking.

Trina remembers that night. She and Hollywood had just finished riding go-carts when he insisted on dropping her off. She wanted to stick around, but he didn't want her to miss school the next day. She reluctantly agreed and remembers falling asleep to one last message from her boyfriend saying he loved her and would see her soon. The next morning, Hollywood's sister called and said, "Turn on the news." Trina rushed to the TV and didn't believe what she was hearing. She just did not believe it.

Hollywood had been slain on a particularly bloody night in South Florida. A half-dozen murders occurred in two hours. "Six people in one night is very unusual," a medical examiner told the Sun Sentinel the next day.

But for Trina, who had somehow skirted Liberty City's darkest corners in her short and joyful life, it was more than unusual. She stayed in her room for weeks and listened to Whitney Houston songs.

Vernesa tried to comfort her, but there are some wounds mothers can't lick clean. "[Trina] took it pretty hard," Vernesa says. "She was devastated."

Trina has always approached the topic of Hollywood with reserve. She spent a lot of time wondering how something so bad could happen to someone so good. "I was young and didn't understand," she says. "To lose someone so close, you don't want to believe that they're gone. But it made me realize that you shouldn't take anything in life for granted... It was one of the hardest things I've had to deal with. Hollywood was a great guy, and he didn't deserve that."

Trick and Lucas, a close friend of Hollywood's, had grown to see Trina as a little sister since she started dating Hollywood. They stayed fiercely by her side in the years after his death and remained there when Trina eventually healed, happiness coming back to her in slow waves.

Hollywood's ambition of building a Miami entertainment empire began to materialize without him. By 1997, Trick's postprison rap career was going better than anyone could have imagined, and his second album, www.thug.com, was about to put Slip-N-Slide on the map. Trick was almost done with the project. He just needed to finish one of the last songs, a track tentatively titled "Nann Nigga."

It needed a female voice, though. The concept was to pit a man and woman against each other, trading blows with each verse in an effort to establish who was the baddest, most ruthless, horniest, and most intimidating. Trick was confident he could deliver, but the song needed a very specific woman — someone who could come at him hard and hold her own; someone with grit and a chin, who could look a bull right in the eyes and snort back.

And he knew just who to call.

Trina stepped to the microphone that night with no agenda. There was no clear plan to overthrow the patriarchy and sweep away hip-hop's long-established gender roles. She was actually nervous, and when they hit that Record button, she just spoke honestly. She'd made it this far in life without a filter and saw no point in popping one on now. So she spoke the way she did among friends — because she was among them. She spoke the way people do in certain parts of Miami, where propriety takes a back seat to efficiency. She spoke the way women address other women in those rare spaces that allow them to be free — like, perhaps, inside a neighborhood salon.

Trina just closed her eyes and did what came naturally. Ask her now and she acknowledges the powerful ripple effect that night had. She realizes how cathartic and refreshing her words sounded to a population that had long been tasked with playing defense — never offense.

But it was really all an accident.

When they played it back just minutes after recording, Trina didn't recognize the squeaky voice. "I was like, 'That's not me. I don't believe you guys. That is not me.'"

But it was. Over five hours, Trina, then age 19, scribbled some rhymes onto a notepad and recorded them. The finished product would prove one of the most astonishing and unexpected verses ever produced in Florida. Unbelievably raw and gloriously low-budget (they recorded it in a closet), "Nann Nigga" quickly uppercut its way through Miami and onto Billboard's Hot 100.

Within the first 30 seconds of her verse, Trina threatens to "fuck 'bout five or six best friends" and brags about being "quick to deep-throat the dick," while "letting another bitch straight lick the clit." And it accomplishes what writers have been trying to do since the ancient Sumerian first chiseled words onto stone: It grabs you by the neck and forces you to pay attention.

It didn't take long for the track, which should have been far too blue to find mass appeal, to become a national hit. Everything happened fast. Trina had recently gotten a job as a real-estate agent, but she never sold a house.

"One verse, she was a star," Lucas says. The first time he heard the song, he felt an equal mix of excitement and dread: the former due to the utter electricity that had just bolted into his ear canal, the latter at possibly mucking up a deal to distribute it. "I could not release the record until I had the contract," he recalls. "It was the second single released off the album because I was in the midst of negotiating, trying to get Trina signed, and convincing her to be an artist."

He eventually wore her down and inked a deal. But then he was faced with a truly horrifying prospect: facing her mom, Nesa, who had always treated him like family.

"I was afraid that she was gonna beat me and Trina's butt — not gonna lie," Lucas says, a hint of fear still lingering in his voice. "She was Mom to me as well... I was thinking, How am I gonna look Aunt Nesa in the face again after this?"

Trick was more confident. Asked if he was nervous about Nesa's reaction, he doesn't hesitate. "No," he says firmly. "Trina was a product of her environment, which includes her mom, her dad, her step-dad, our neighborhood, the Pac Jam. This was our life."

Trina strategically played her mother the censored version at first. "She was like, 'Why are there all those spaces? What's it beeping out?'" the singer recalls.

Eventually, the song became too popular to hide. People approached Nesa, beaming, to say they had heard Trina on the radio. She understood her daughter was onto something.

"I think it took me maybe two months before I even went around [to see] Nesa," Lucas says. "You know how when you know you're gonna get a beating, you try to let your parents calm down first? But by that time, she had already got over it... I think she opened her arms and hugged me, and thanked me for seeing something in Trina."

While others were quick to recognize her as a rising star, there was little time for Trina herself to adjust to her new reality. Just weeks after "Nann Nigga" dropped, she was out on the road with Trick, touring and performing for the first time in her still-teenage life.

Just before they left to work their way up the state, Trick Daddy threw a birthday party for himself in Miami. It had been just a month since the song was released, but the club was packed. Trick planned to perform that night. Trina did not.

"They set me up," she says. "I was like, 'I'm not getting onstage. I don't care what you guys say.'"

But her protest fell on deaf ears. The instrumental for "Nann Nigga" started, and the crowd went nuts. Trick performed his verse, and then it was time.

"Now the part comes on, and they push me like, 'You have to go!' And I'm like, 'No, I'm not going out there.'" They eventually shoved Trina onstage, and she froze. Her verse was about to drop. She shut her eyes tightly — a nervous tick that would stick with her for months. "I'm shaking," she remembers. "The whole thing, I don't say a word."

She finally opened her eyes — just for a second — and she'll never forget what she saw: "All the girls in the audience are singing the song word for word, screaming at the top of their lungs." The track had been out only a month, in pre-social media, pre-SoundCloud America, and they knew every word. Every. Single. Word.

And it was always the women. Throughout the tour, they showed up, loud and proud, singing lyrics that not too long ago in the spectrum of human history (or today in some parts of the world) would have gotten them stoned to death.

Those first shows were formative, if a bit perplexing. Here, Trina thought, I'm saying all these things I've been told my whole life are not what a person like me is supposed to be saying. Yet look at them. They love it.

"I was trying to figure it out," she says. "Like, Do all these women talk like me? I'm just trying to figure it out because it's my verse, it's very provocative, it's Luke's Miami, it's strip clubs, it's all that. That's the culture. And because I'm so aware of it, I'm not in fear of it. So I'm thinking I must be the only fearless person here because I got the balls to say this, and all the rest of these people are just living vicariously through me."

Well, she thought, that must be it. So she decided the next step was simple.

"Just go harder."

It should be in a museum, really. That first album cover is as perfect a work of art as anything to come out of the Renaissance. A brief summary: Trina, dressed in 50 percent of a paramedic's uniform, straddles a bloodied man lying on a gurney outside an ambulance. He has some sort of head injury and appears to be unconscious. Trina stares hungrily out from the photo, her tongue feeling its way around the corner of her mouth as if searching for a crumb. She is holding two defibrillators to the man's chest. They are seemingly hooked up to nothing but the raw sexual energy of Trina herself. In the upper right-hand corner, there's an odd little graphic that looks like the grandfather of every questionable lower-back/upper-arm tattoo you've ever seen. The words "Da Baddest B***h" are hammered into the bottom of the photo in a font accessible only if you punch Microsoft Word in the face and force it to drink grain alcohol.

The CD behind that album cover did not disappoint either. It was a worthy followup to Trina's breakout success. Da Baddest Bitch reached number 33 on the Billboard 200, earned her a deal with Atlantic Records, and tapped into a powerful audience.

Its 15 songs furthered Trina's reputation as a sexual wolverine, lyrically speaking. Track 2, "Da Baddest Bitch," was a mission statement of nuclear proportions that earned her a nickname that endures to this day. Each verse is packed with multiple jaw-droppers.

In Verse 1: "See, I fuck him in the living room/While his children home/I make him eat it while my period on." And Verse 2: "X-rated, elevated, buck naked/And I'd probably fuck your daddy if your mammy wasn't player hatin'." Finally, the pièce de résistance: "I never took it up the ass/Often tried but I pass/And from what I heard it ain't bad."

But if you look past the shock value, Trina's impressive lyrical agility was on full display in her debut LP. It wasn't all sex either. "Mama" was a touching ode to her mother that feels more like gospel.

It was the beginning of what would prove to be a long career in an industry not known for longevity. In the past 19 years, Trina has done what Miami artists seem to have a special ability to do: remain relevant by sheer force of will. She has released more studio albums than most of the female rappers in her class — more than Lil' Kim and Eve and Foxy Brown and Remy Ma. The only associate who's been able to match her output is Missy Elliott, who is herself a huge fan.

"The first song I heard from Trina was 'Baddest Bitch,' and my initial reaction was, Who is this chick with these ratchet-ass lyrics?" Elliott says. "But as I was saying that to myself, I was bopping my head, like, this joint go hard!"

The album furthered Trina's reputation as a sexual wolverine, lyrically speaking.

tweet this

Elliott, like many, was pleased to discover a female voice had barged into a room previously occupied only by men. "When I heard 'Pull Over' — it was that Miami vibe, which we hadn't heard from a female. We heard Luke and Trick Daddy, but not from a female. Musically, that was refreshing to my ears."

Throughout the '00s, Trina never went more than three years between albums. Every time it looked like she might slip below the water line of relevance, she kicked her way to the surface. "No Panties" became the anthem of her sophomore album, Diamond Princess. There was the Kelly Rolland collaboration, "Here We Go," in 2005. "Look Back at Me," featuring Killer Mike, made 2008 squirm in erotic giddiness.

But by 2010, after the release of her last studio album, Amazin', something had changed. "I had grown lyrically, musically — everything," she says. "I wanted to still be saucy and be me, but it was a little bit less," she thinks for a moment about how to put it. "The lyrics were a little toned down... Me and the label weren't really seeing eye to eye."

Trina, as people do, matured. And she felt Slip-N-Slide hadn't kept pace. "At that point, I said to myself: You've changed. You've grown. You are the baddest bitch, but you are a woman, and you understand you're vulnerable and sensitive. And you want people to understand and respect that."

She walked into Ted Lucas' office one day and delivered the news. Trina was now an independent artist. Was he disappointed? "It was more than disappointing. I was HURT," he says. "You can put that in big, bold letters."

Perhaps Trina expected to feel free now, unbound by expectation and finally able to be the artist she was meant to be. And she did — for a while.

Then that little voice in her head grew louder. Throughout her career, Trina had a team behind her, and not just any team — her team. They were family. And they guided her each step of the way. "Now I'm thinking, Damn, how do I continue to do what I love to do, not signed to a label?"

She had the capacity, of course. We're talking about Trina, after all. She'd need the entire reservoir of her mental and emotional energy, every ounce of fortitude and confidence she could muster. But right when she was about to reach in and grab it, it was stolen from her.

Trina got the news soon after it happened the morning of April 23, 2013. Her brother, Wilbrent Bain Jr., had been shot and killed on NW 91st Street after an argument. Neighbors said the two men had been friends before their relationship began to sour.

"I was totally lost. I was at a dead place. I didn't care. I didn't want to do music. I didn't want to do anything."

And thus began a very long gap in Trina's discography. In the wake of the tragedy, she second-guessed herself into the worst writer's block of her career. No song seemed good enough, no lyric worth recording.

"She's so hard on herself," says Evans, her friend from Carol City who is now Trina's road manager. He watched for years as she tried to dig her way out of a creative rut. "She'll second-guess and second-guess and then, next thing you know, it's been two years. Then someone comes out with a record that sounds too similar to hers, and now you're at four years."

There were other distractions too. Trina's personal life began to grab headlines over her music career thanks in part to a public split from former NBA all-star Kenyon Martin. Interviewers still insisted on bringing up her engagement to Lil Wayne at every turn despite the fact that relationship ended in 2005. And, on top of all that, her cell phone was stolen and alleged nude photos from it were leaked online.

"Eventually," Evans says, "it got to the point where it was like, OK, if you're gonna do it, do it. If not, hey, it's time to move on."

But what would she move on to? Trina would always be Trina, and there was no running from that. "I had to say to myself: Trina, you're extremely smart. What are you doing?"

Not surrendering, she decided. So she drew up a game plan: "Get in the studio, focus, get your team together, let's go make it happen."

By 2016, she had pulled herself together. On the 16th anniversary of Da Baddest Bitch, she released the single "Overnight." Compared to some of her bigger hits, the song flew under the radar. But it is one of the most revealing and emotionally bald pieces of her entire body of work. The reflective three-minute song is a cathartic dump of every piece of baggage that had dragged her down in the prior five years: label disputes, murder, legal woes, and jealousy.

The accompanying music video is a somber black-and-white tour of Liberty City that ends with the image of a young black man lying dead in the street, a splatter of blood soaked into the breast of his white T-shirt.

It's both a grim reminder of the many who never made it out of Trina's hometown and a defiant celebration of those who did. What would she say now to a girl living on those same streets that raised her?

"The real test is if you can survive through the hardest parts," she says. "The yes is always good. Somebody says yes — you feel like you're on a roll. When you get that first no, if you can pass that, that's when you really know you're onto something."

By proclamation, May 15 was recently named Trina Day in the city of Miami. A month later, at the ultrabougie South Beach steakhouse Prime One Twelve, close friends and family gathered to re-create the occasion for Trina's reality show, Love & Hip Hop. Miami Commissioner Keon Hardemon, who hails from one of Liberty City's most powerful political families, was there to present the award for the cameras. As he tripped through his speech, he made the fidgety eye contact of a young man who has accidentally stumbled into the women's bathroom and discovered it full of every single one of his celebrity crushes.

"I had all these people screaming they're the baddest bitch."

tweet this

Nesa sipped a Shirley Temple as she sat by her daughter. She looked glowingly proud and impossibly youthful — so young that a reporter who had been researching her for months could spend a solid ten minutes standing next to her at the bar, thinking to himself: I wonder where Trina's mom is?

It is impossible to know how many women have been galvanized by Trina's work. But when one looks upon the empowering sexual individualism of today's most influential female artists, it is not very difficult to trace a path back to her. Her influence has extended beyond music too. In 2006, she founded the charity Diamond Doll, which, according to a quaking description from Commissioner Hardemon, "allows young girls to talk about and deal with the struggle of puberty, teenage pregnancy, drug and alcohol use, domestic violence, and, of course, education."

Still, legacy isn't something Trina thinks too much about these days. She's focused on her new album, The One, which will drop within the next two months. Perhaps you've heard its first single, "Damn," a collaboration with Tory Lanez that has the makings of a national hit and, at the moment of this writing, has garnered 3,296,264 Spotify streams. Also, in a wonderfully circular story arc, a reunion album with Trick Daddy will be released this year on Slip-N-Slide, which makes Ted Lucas happy in a big, bold way.

When Trina does get nostalgic and peeks into the rearview mirror, this is what she sees: "It was just the fans — the women. They would be crying, falling over, writing letters. And I'm like, Wow, I've changed a whole demographic of women. I had all these people screaming they're the baddest bitch."

You know, Trina's career presents a strong case for the power of affirmation. Was she always the baddest bitch, or did she just say it enough times and with such conviction that one morning it was simply fact? It's possible it was hibernating, fully formed, within her this whole time. It could also be that she hunted that seed down, planted it with her bare hands, and watered it with sweat and tears. Let's assume the latter is true. Let's assume the quality of being a bad bitch is not intrinsic, but can be taught and cultivated.

That's the more exciting option. Because if it's fact, Trina's legacy doesn't stop at this album or the next. It means a whole new generation of bad bitches is out there, just waiting to unleash their full force upon the world. And how exciting is that?