“Do you feel that what you have to say in your films will continue to be different from other filmmakers?” Barbara McCullough asked Julie Dash around 1979 on The View, a student cable program at UCLA, home of the L.A. Rebellion movement — a constellation of black auteurs, like two women in this segment, who studied film there between the late 1960s and the late ’80s. Dash, 26 or 27 at the time of this conversation, was in between projects, having completed her short Diary of an African Nun, an adaptation of an Alice Walker story, two years earlier, and in the earliest stages of preparing what would become the 40-minute-long Illusions (1982), a shimmering period piece about two African-American women working in World War II–era Hollywood that incisively lays bare the myths about race and gender perpetuated by the movie industry. Dash’s reply to McCullough is unequivocal: “Of course. That’s the reason I’m making these films and will be making films. What we have to say is so personal and so very different that there’s no way that anyone else can say it, and they can’t say it for us.”

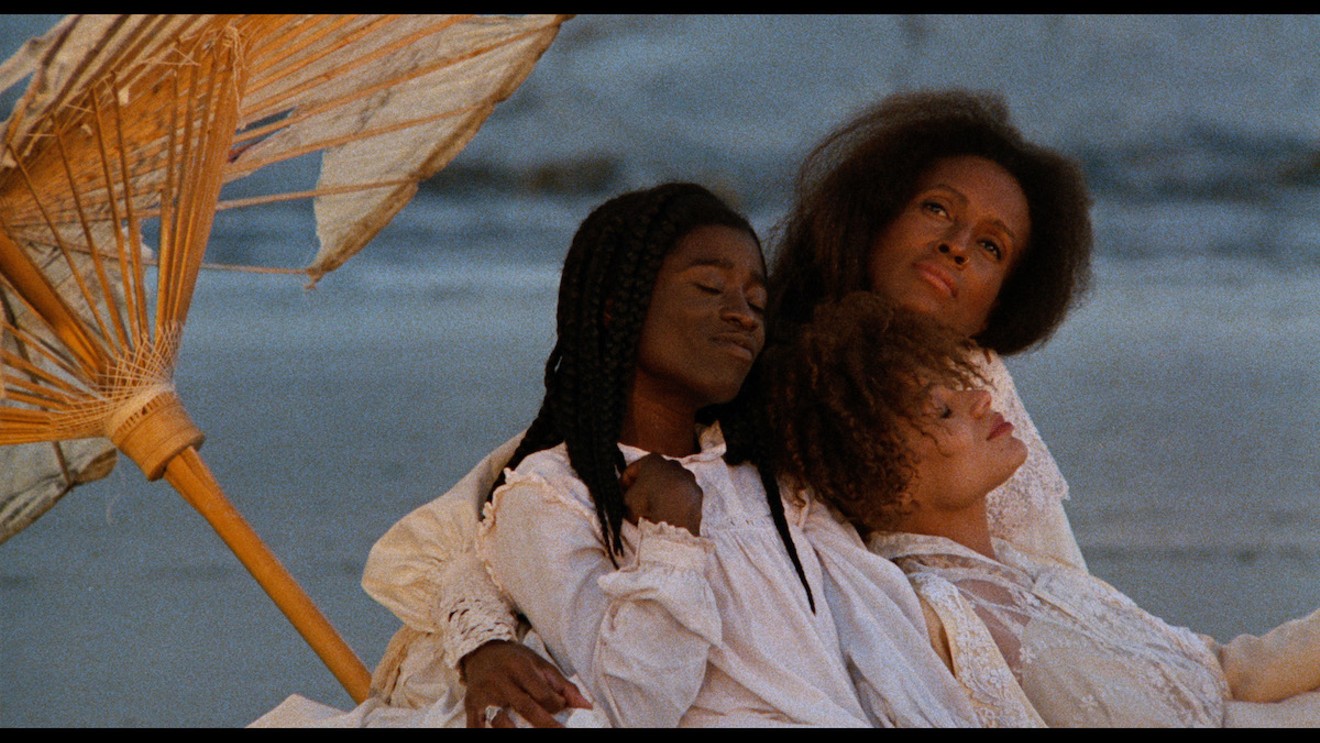

So personal, so very different: It took Dash more than a decade to make her oneiric and lush mythopoetic masterwork Daughters of the Dust, which, after premiering at Sundance in 1991, became the first feature directed by an African-American woman to receive a wide theatrical release. The movie returns in a 2K restoration, the colors and textures of this immensely sensuous project (originally shot on 35mm by Arthur Jafa) more vibrant than ever.

A nonlinear tale of past, present, and future, Daughters of the Dust takes place in 1902 on one of the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina. It is here that the Peazants, a Gullah (or Geechee) family — descendants of slaves who have continued the practices, spiritual and otherwise, of their forebears’ West African cultures — gather for a farewell feast before most of its members depart for a new life on the mainland. The clan’s matriarch, Nana (Cora Lee Day), however, will not be moved by her brood's promises of progress and stays put. Her actions are as resolute as her words, like the powerful declarations that conclude her opening off-screen monologue: “I am the silence that you cannot understand. I am the utterance of my name.” The sentences are as elemental as the dirt she holds in her hands.

Another off-screen voice will soon be heard, in one of Dash’s bolder conceits: that of the Unborn Child, an emissary from the near future who sometimes appears as a smiling little girl darting in and out of the frame. She materializes when Mr. Snead (Tommy Redmond Hicks) — the photographer enlisted by Viola (Cheryl Lynn Bruce), Nana’s Philadelphia-dwelling, fervently Christian granddaughter, to document the family reunion — lines up a shot of Peazant men, only to vanish a blink later.

The totems of the past are just as unconventional and no less potent. A flashback shows men and women toiling in an indigo-processing plant, the hue permanently tattooed on Nana’s hands. “The color…is my way of signifying slavery, rather than by whipmarks or scars, which are images that I believe have lost their power,” Dash explained to Sight and Sound in 1993.

Daughters of the Dust abounds with stunning motifs and tableaux, the iconography seemingly sourced from dreams as much as from history and folklore. But however seductive and trance-inducing, the visual splendor of Dash’s film is never vaporous. She is particularly attuned to the movement and carriage of bodies — so much so that my memories of, say, the regal posture of Yellow Mary (Barbara O., who played the main character in Diary of an African Nun and 1979’s Bush Mama by Haile Gerima, another L.A. Rebellion alum), a “ruin’t woman” returning to the Sea Islands with her girlfriend, have remained undimmed since I first saw Daughters of the Dust — quarter-century-old impressions that, as my very recent second viewing of Dash’s movie confirmed, closely adhered to what’s on screen.

Dash teamed up with a trio of prominent African-American visual artists for the production design, including the great large-scale painter Kerry James Marshall; the arrangement in the frame of multiple generations of Peazant men and women, all clad in white, in postprandial languor suggests Renoir canvases of bodies in repose. Though the mood and rhythms of Daughters of the Dust are largely serene, just beneath the quietude buzzes the anxiety of a family being fissured, of loved ones pulled apart by their allegiance to tradition or modernity.

As I am the millionth person to point out, Beyoncé repurposed much of the look — the small groups of stalwart women in floor-clearing dresses, the fecund scenery, etc. — of Daughters of the Dust for segments of Lemonade. It’s a fine salute to Dash, but this singular filmmaker has a tribute of her own in the works, to one of her DotD cast members. Listed in the credits as “Hair Braider,” Vertamae Grovesnor, an incomparable performer and writer who died in September, will be the subject of Dash’s documentary The Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl, the name a recycling of the subtitle of Grovesnor’s 1970 cookbook/memoir Vibration Cooking. Undoubtedly, the project will be a lovely coda to Daughters of the Dust, another of example of Dash’s uncanny way of making sense of past, present, and future.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "19274298",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17482312",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482310",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482313",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]