That exposé kicked off a glittering career as a foreign correspondent that would see Allman file news stories from more than 80 countries for Esquire, Vanity Fair, the New Yorker, and other prominent publications. Over the ensuing 40 years, the Harvard-educated Florida native rescued victims from a massacre in Cambodia, survived a kidnapping in Beirut, took a bullet in Beijing's Tiananmen Square, and investigated drug kingpins in the lawless hinterland of Colombia.

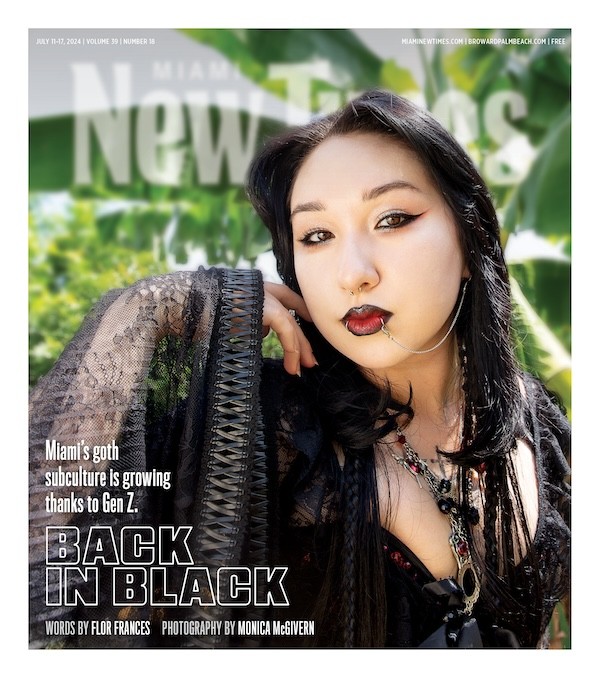

But in Miami, Timothy Damien Allman is best remembered for Miami: City of the Future. A tour de force of literary journalism published in 1987, Miami was a meticulously researched and exquisitely written portrait of a metropolis widely thought to have been rotted to its core by wanton crime, rampant corruption, and urban decay.

Allman saw a very different Miami.

"Apart from its biting observations and deep reporting, the book ran counter to what everyone else was saying about Miami," says veteran journalist Jim DeFede, recalling that the then-editor of this newspaper, Jim Mullin, admonished him to read the volume when DeFede joined Miami New Times in late 1991. "According to the rest of the world, Miami had no future. But Allman understood that all of the problems that made everyone else write Miami off were actually the seeds of its greatness.

"Yes, Miami was violent and corrupt; it was the canary in the coal mine for so many issues — drugs, addiction, homelessness, immigration, race," DeFede says. "But it was also sexy and cool, and how Miami dealt with its challenges would offer a glimpse into America's future. Reading Allman made me realize this was a city worth understanding."

The celebrated author and journalist died on May 12 in a Manhattan hospital. He was 79 years old. The cause of death was respiratory failure, according to his partner of 25 years, John Sui.

An Accidental Floridian

Born in October 1944 in Tampa to U.S. Coast Guard officer Paul J. Allman and his antiques-dealer wife Felicia, Timothy moved with his family to Pennsylvania at age 5. He could claim only the most tenuous of links to the Sunshine State when he landed in South Florida in the mid-1980s to start work on the Miami book. (The adult Allman once described himself in print as an "accidental Floridian.")But the already well-traveled bon vivant instantly took to the city, says Andres Viglucci, a veteran Miami Herald reporter who was working in the newspaper's Miami Beach bureau when he first met Allman.

"Somebody suggested he contact me. We kind of hit it off, and I started driving him around," says Viglucci, who, along with his wife, fellow Herald reporter Linda Robertson, became close friends with Allman. "Miami was a dark and surreal place in a lot of ways back then, and he keyed in on some of that. He always liked Miami."

Another early contact for Allman was Woody Graber, a Buffalo native who'd moved to the area in 1979 and was working for the Miami Beach Community Development Corporation when he met the high-flying foreign correspondent. The nonprofit MBCDC at that time was in charge of conserving and refurbishing many of the famous art deco buildings that lined the streets of South Beach, and the campaign to save iconic hotels like the Cardozo and the Carlyle from the wrecking ball captured Allman's imagination.

"Tim was researching everything he could about South Beach, and he was very much interested in what was happening with historic preservation," says the now-retired South Florida publicist. "At a time when the world was calling us 'Paradise Lost,' he saw Miami for what it could be, not for what it was."

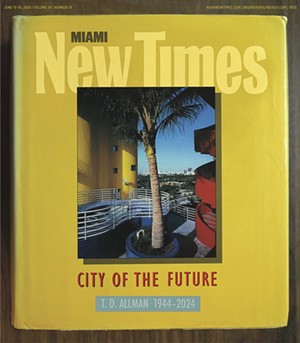

The cover of the June 13 print issue of Miami New Times commemorates the original edition of Miami: City of the Future, first published in 1987.

Photo-illustration by Tom Carlson

There is Isaac Bashevis Singer, the diminutive Nobel Prize-winning novelist who wrote in Yiddish with a fountain pen and sometimes treated visitors to a bowl of borscht at a restaurant in the affluent suburb of Surfside.

And then there is "the Helpless Hooker." In the epilogue to City of the Future, Allman recounts his quest in the company of Viglucci for a sex worker who used a wheelchair and whom the Herald reporter had described as "very pretty, even though she can't walk." Like a lot of the other prostitutes plying their trade along Biscayne Boulevard in the '80s, this woman would hang out at bus stops so that if a suspicious cop were to accost her, she could plausibly say she was merely awaiting the next Metrobus.

The book also displayed the author's unfailing eye for the bizarre. On another occasion, when he was riding shotgun with Viglucci, they stopped to feed a quarter into the tollbooth at the mainland end of the Venetian Causeway and Allman came face to face with a vehicle transporting a large number of big cats.

"I saw we were surrounded by tigers," Allman writes. "There were dozens of them — sleeping, stretching, scratching themselves, yawning, staring listlessly at the blinking neon city that reared up in front of them.

"The eyes of the tigers were expressionless," the account continues. "[They] no longer questioned their cages. Even when their cages were put on trucks and carted across Venetian Way to the next exhibition of the Ringling Brothers Circus, they found no wonder in the world, not even when all the wonders of Miami rolled past them."

A Local Bestseller

Locally, the reception that awaited Allman's book verged on the rhapsodic, at least in some quarters. "An extraordinary look at an extraordinary city," gushed Edward James Olmos, the Mexican-American actor who played Lieutenant Castillo in the hit TV show Miami Vice. Books & Books owner Mitchell Kaplan (whom Allman thanked in his book's acknowledgments section) remembers Miami: City of the Future as "a bestseller" for the bookstore because it offered "a complete history of Miami that hadn't really existed before."Xavier Suarez had just begun his first term as Miami mayor in 1986 when he granted Allman an hourlong interview at his bayside office. He says he didn't encounter a single inaccuracy or the slightest hint of personal bias in the 422-page book, which he compares favorably to Alexis de Tocqueville's magisterial two-volume opus Democracy in America.

"He wasn't just into interviewing people; he was living Miami for the better part of a year," the city's first Cuban-American mayor notes. "Joan Didion and others wrote nonsensical things about Miami that they picked up from the Herald or Miami's community newspapers. But Allman didn't start off disliking the city, and his book wasn't about him. It was about Miami, and there was nothing distorted, exaggerated, overly critical, or hagiographic."

The manuscript absorbs the reader because Allman brought to the task at hand an ace reporter's insatiable curiosity about his chosen subject matter.

"He was a first-rate journalist," says Graber, who spoke by phone with the hospitalized Allman for the last time a few days before he died last month. "He wanted to know everything about the government and politics of Miami and the players who were making things happen."

But there was also an unorthodox side to Allman's modus operandi as an interviewer. "He did not take notes," Viglucci says. "He thought people were more guarded if you were writing things down. So he would go to his hotel room afterward and write everything down from memory."

He once asked Allman about that unusual journalistic practice, which seemed all the more remarkable in light of the richly detailed chronicles contained in the four books he published during his lifetime. "He told me, 'I just prefer to have a conversation and let people open up.'"

A Lasting Love Affair

The author's love affair with the city did not end with the publication of the book in 1987. He continued to visit Miami on a fairly regular basis, acquiring a 39th-floor apartment in Miami Beach's Akoya condominium tower in 2009, and over time he assembled a motley crew of friends and acquaintances. (In 2013, he also published Finding Florida: A True History of the Sunshine State, to some controversy.)"He had this larger-than-life personality, and he would gather this disparate group of people and hold court," says Viglucci, who occasionally hosted the author at his Coral Gables home. "He had traveled all over the world, and he loved to tell stories or prompt other people to tell their yarns."

Allman sold his Collins Avenue apartment in 2021, and by that time, his attention and energies were primarily focused elsewhere. He was applying his prodigious talents to researching and writing a new book about an 800-year-old house he'd purchased in the medieval hilltop village of Lauzerte in southwestern France.

Entitled In France Profound: The Long History of a House, a Mountain Town, and a People, the book does two things: It narrates Allman's personal experiences with the dwelling and the inhabitants of Lauzerte, and it uses the town and its environs as a vehicle to recount the turbulent history of the region dating back to the 12th-century reign of England's King Henry II. It will be published posthumously by Grove Atlantic in August.

Allman was a heavy smoker for the better part of 30 years — and though he'd quit by the time he met the Chinese physicist John Sui in 2000, his lungs began to seriously trouble him during the first quarter of this year. Allman returned to Miami for the final time in the early spring to reminisce about the city at a public event sponsored by Florida International University's Maurice A. Ferré Institute for Civic Leadership.

Miami-based filmmaker Aaron Glickman attended the April 2 event and interviewed the ailing author during his stay. "He couldn't breathe. He couldn't walk. He was in bad shape," the digital media publisher recalls.

T.D. Allman is survived by his brother Stephen and his sister Pamela. His legacy in the context of Miami can be best captured through his own words.

"These days, for both good and ill, Miami is America," Allman wrote 37 years ago. "Like America, it's fast, big, new, reckless, thoughtless, and even kind of scary. But Miami's also got America's saving graces. There's something about the place that engenders cooperation and invention, excites the imagination, and produces hope.

"Miami will go on getting more and more 'American' — and not just because Miami is becoming more and more like the rest of the country, but because the rest of the country is becoming more and more like Miami. Other American cities already are discovering that they, too, have Hispanic voters and that there is big money to be made in foreign trade.

"You have to come to a place like Miami, seemingly so 'foreign,' to appreciate that extraordinary power, that all-pervasive — completely subversive — force of what can only be called American civilization."