Inside the 50,000-square-foot industrial building reside immersive and experiential art installations: flowers that wilt and revive in the span of minutes, a two-story mirror maze resembling lungs, and a depth-defying, color-changing room where meditation becomes therapy. But beneath the concrete infrastructure rests a layer of soil once worked by Black laborers and cared for by indigenous people.

Through the short film Every Step Is a Prayer, artists Lilleth, Rad Pereira, Niki Franco, and Houston Cypress celebrate the Black and indigenous histories of South Florida, proclaiming a movement for queer joy and liberation while redirecting the role of art institutions back to the communities they inhabit. The short film, a collaboration with Superblue and Nowness that was directed by Cara Stricker, welcomes viewers into the lush wetlands of the Everglades, the urban matrix of Allapattah, and the immersive installations at Superblue.

Before Superblue opened, the museum's managers were aware of what its presence might evoke in a rapidly gentrifying community. Curators reached out to Brooklyn-based artist Lilleth and Pereira, a South Florida native, to see how Superblue might engage with the community in a regenerative fashion.

“We were kind of tasked with this question of: How could an art institution do that in an ethical way or, you know, in an aspirational way?” Lilleth says.

Pereira and Lilleth immediately reached out to Franco and Houston, local artists and organizers already having conversations around artwashing and how the cultural industry interacts with communities.

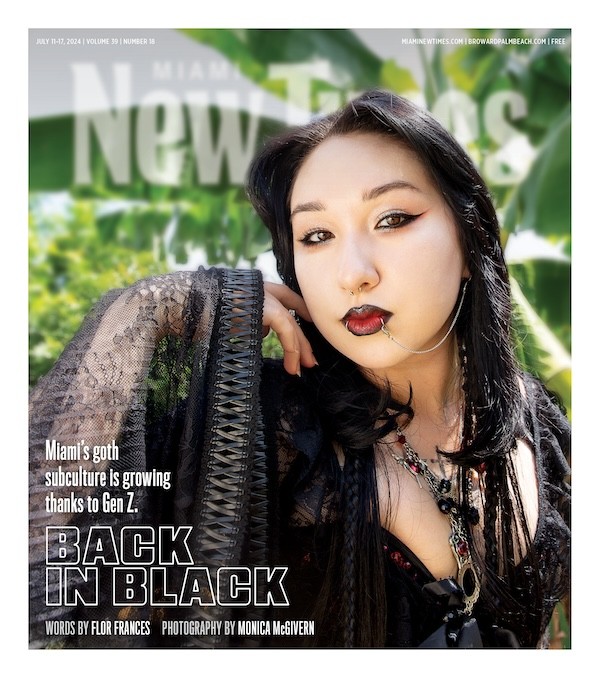

Still from Every Step Is a Prayer, featuring Niki Franco.

Photo courtesy of Michael Cambio Fernandez

The techno-surrealist film's narrative was inspired by the fate of Maroon people — escaped Black slaves who took shelter in the seemingly harsh terrain of the Everglades and were welcomed by the Seminole and Miccosukee people. The land seen as harsh and brutal by colonial forces was actually a site of survival, new life, and renewal.

“I think one of the most fascinating stories of revolutionary resistance of solidarity here on this land is the story of Maroon communities, and how that solidarity gave birth to a lineage of resistance and to this day, Seminole and Miccosukee people being undefeated in the face of colonialism,” says Franco, who works with Fempower and PowerU. “We recognize that this is not the totality of it. This is just kind of an opening of a door, the opening of a portal.”

The Everglades wilderness comprises a vast majority of South Florida, but there remains a resistance on the part of locals and tourists to engage with the land. For some of the cast and crew, the film was their first time there. Franco notes the parallel between a reluctant popular opinion of the Everglades and how colonizers once described the land as brutal and uninhabitable. Pereira reflected on this tension throughout the filmmaking process.

“I think that's just one of the ways that colonialism tried to take us away from the land and try to forget our grandmother's songs,” Pereira says. “I have now made friends with that land. And with that place that is not water nor land and that there's so much power and beauty and lessons to learn from that in-between place.”

On a pitch-black morning in April, before the sun had emerged above Miami’s horizon, Pereira arrived at Franco’s home near where Liberty City and Little Haiti converge and just a few blocks from Allapattah (the Seminole word for alligator). Pereira was picking up Franco up extra-early, eager to get to the Everglades before sunrise for their first day of filming. On their way, they paused for coffee and rituals. Once on Miccosukee land, they watched the sunrise over the wetlands, illuminating the beauty of their surroundings, collaborators, and their intimate creation process. Cypress, a Miccosukee artist and organizer, began the day by asking permission of the land to film, in line with their community’s protocol when working with nature. In between filming on 35 millimeter, performers held vulnerable conversations about identity and their histories, deepening their connection to one another. While filming, affirmations rang high. By the end of the 16-hour day, Franco determined this was one of the best days of their life.

Still from Every Step Is a Prayer, featuring Arielle Franćois.

Photo courtesy of Michael Cambio Fernandez

Cypress refers to the foursome as the “dream team.” Seldom are film sets so intentional, even the decision to shoot on 35-millimeter film was rooted in a desire to represent a sense of truth and rawness. The four friends and collaborators cultivated a somatic practice with a sense of integrity and trust for everyone involved. The eight-and-a-half-minute film is a testament to their ability to hold space for performers to metaphorically and sometimes literally “dance across dimensions.”

Fifteen seconds into the piece, dancer Tarik Boom stands in profile amid an indigo void in James Turrell's installation inside Superblue, “Akhu.” The performer at first appears solitary — almost statuesque, save for his deep, undulating breath. But, two and a half minutes later, the score quickens. As Boom takes a step forward, seven performers take measured, synchronous steps forward and back to reveal the collective connected behind him, forming an angled line.

“It takes a lot of connection to the other performers, a hyperawareness, which our performance was already about that because of what Lilleth created with this slow movement and just trusting each other for direction like birds,” dancer Lau Narciso says.

This movement, choreographed by Lilleth, reflects a question at the heart of the film and Superblue at large: How can the art world move from a singular scarcity economy of a single painting or individual to an experiential economy that's focused on the collective?

“Even though we're dealing with a lot of dualities like our individual selves versus the collective — like nature versus the built environment, like being awake versus dreaming — I think that what resolves these contradictions is a sense of spirituality that embraces these contradictions," Cypress explains. "And the kind of spirituality that I'm talking about is our journey as people, the beautiful trauma and the beautiful opportunity that birth represents. The beautiful trauma and the beautiful opportunity that coming out as an LGBTQ or nonbinary person represents and how we can choose our families to find that sense of nurture that we need when we're growing up. There is a journey that we all find in common as people that kind of resolves these contradictions.”

Thirty-three seconds in, Franco recounts the history of the Maroon people through spoken word as dancer Arielle Francois appears onscreen. With Francois’ eyes closed, she lifts her hands, palms open in reception with just a single leaf held gently between her right forefinger and thumb. As narrator Betty Osceola describes the relationship between nature and the body, declaring that the Earth has a heartbeat, Francois passes the leaf to her left hand. She leans back as her bulbous gown glitters like azurite over the river of grass behind her. For a minute and eight seconds, she levitates over the water.

“I think the energy of the collective is a lot more powerful than any location because, to be honest, this is all Miccosukee land. So it doesn't matter where you go," Francois says. “As Rad [Pereira] would say, if you put your feet on the earth and you are feeling deep into the core of the earth, you're placed exactly where you need to be. That is really where I was traveling. Even the camera was traveling there.”

Francois filmed that scene on the edge of an airboat with the camera above her. Franco recalls screaming and clapping in awe of Francois’ performance in the moment. The elder airboat driver joked he had never seen a happier group on an airboat.

“That’s just queer joy,” Franco explains. “Everyone felt it.”

As part of Lilleth’s slow-moving, meditative choreography, Cypress offered Miccosukee symbols typically used in patchwork textiles for performers to embody, referring back to the natural world. Lilleth reflected the symbols through the performer’s placements and movements to symbolically point to the land.

“What happens when we slow down enough that we kind of move into a more liminal realm where we can better listen to the land, our bodies, our ancestors, the space between us, in order to unlock something there?” Lilleth says. “That is what is so easily erased in a fast-paced capitalist world that we live in. So I think we were wondering, is there a way to literally go into this space and reveal the land beneath the building?”

In the future, Pereira, who's the consulting director of community engagement and learning for Superblue, envisions community partnerships that would address Allapattah's pressing needs. They want to bring a community fridge to Superblue and plant a native food garden that youth and elders in the area can have access to. Owing to the pandemic, those plans are still in development.

Cypress looks forward to continuing to "dance across dimensions" together. The rest of the "dream team" is similarly eager to see how this film will begin critical conversations in the community.

As the film closes, indigo fades to violet in Turrell’s “Akhu.” Boom crumples to the floor, but perhaps this pause is cyclical — if nurtured carefully, his bloom is imminent.

Every Step Is a Prayer can be streamed via Nowness.com.