No one knows what was discussed in that room, but One Night in Miami fictionalizes what may have transpired that night. Oscar-winning actress Regina King (Watchmen, If Beale Street Could Talk) makes an impressive feature directorial debut with this screen adaption of Kemp Powers' 2013 one-act play of the same name.

The film centers on the four men, all of whom face intense struggles at the apex of their careers. King introduces each of these larger-than-life figures through humbling backstories that represent moments of failure or uncertainty. In the opening scene, Clay (Eli Goree) showboats at a London fight and his opponent unexpectedly knocks him flat. Singer Sam Cooke (Leslie Odom Jr.) flops in his performance for an unwelcoming white audience at the Copacabana, his dream venue. Celebrated NFL star Jim Brown (Aldis Hodge) discovers that his accomplishments do not spare him from everyday Southern racism. An increasingly isolated Malcolm X (Kingsley Ben-Adir) plans his exit from the Nation of Islam while the press denigrates him on national television.

Each man teeters, terrified and unsure, on the precipice of major life shifts.

Ben-Adir’s portrayal of Malcolm X might be the most interesting performance of the film. Several actors allegedly shied from the role because they did not want to follow Denzel Washington’s powerhouse performance in Spike Lee’s 1992 biopic Malcolm X. King initially approached Ben-Adir for the role of Cassius Clay, but the complexity of Malcolm’s character appealed to Ben-Adir on a deeper level. So much of Malcolm’s public persona was his trademark tough façade, but Ben-Adir’s interpretation explores a sensitive side.

“Malcolm, as a husband and father, was so much of my conversation with Regina before she cast me,” Ben-Adir says. “She wanted to make sure that the actor playing Malcolm understood that this film really required a different heartbeat. We wanted to try and tap into that humanity of Malcolm in danger and what that might have felt like for him.”

Ben-Adir’s Malcolm is conflicted and forlorn. With his split from the Nation of Islam imminent, Malcolm fights to keep himself and his family safe. His hope is that Clay will publicly announce his conversion to Islam and join him as he starts his own Muslim organization.

“The process of working with Regina [King] and working on Malcolm in this film was the most intensive, full-on acting experience that I have ever had,” Ben-Adir admits. “Regina allowed us to concentrate on the humanity of these men and what their fears, hopes, and dreams may have been at the time.”

With much of the movie set in a modest hotel room, King trains her lens on the intricacies of Black fraternal bonds. Confined to the room, the men must deal with one another and with their own self-doubts. The biggest conflict occurs between Malcolm and Cooke, who at face value have little in common. Yet, both men grapple with where they fit in the movement for Black equality, and within a year of this meeting, both men are tragically murdered. As in the play, Miami’s Hampton House serves as a liminal space for the men. Each of them emerges forever changed.

Although King shot her film in New Orleans, its Hampton House setting is a real Miami landmark. During its heyday, the motel was a premier destination for Black talent visiting the city. It served as a base for luminaries like Martin Luther King Jr., Sammy Davis Jr., Nat King Cole, Marvin Gaye, and Althea Gibson. From the 1950s to the '70s, the Hampton House thrived as an after-hours hangout for community members and celebrities. Often, musicians held impromptu, late-night jam sessions in the motel’s lounge.

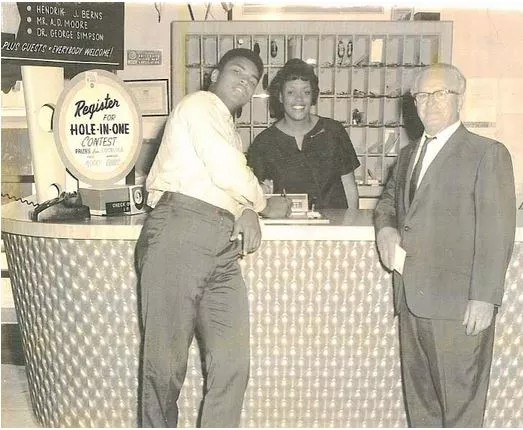

Cassius Clay at the Hampton House after his 1964 heavyweight championship victory over Sonny Liston.

Photo courtesy of Historic Hampton House Cultural Center

Desegregation dealt a huge blow to Black oases like the Hampton House. Black artists and visitors opted to stay at upscale places like the Fontainebleau, and the Black residents who frequented the motel to socialize left Brownsville for communities that represented upward mobility. The hotel shuttered in the 1970s.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the abandoned building attracted squatters and drug users. By the early 2000s, the Hampton House was on the brink of demolition, but a grassroots campaign to save the landmark succeeded. After a multimillion-dollar renovation and a 15-year battle, the Hampton House reopened as the Historic Hampton House Cultural Center in 2015. The center serves as a museum where visitors can tour Ali's and King's rooms and access photographs and paraphernalia from the motel’s glory days.

Enid Pinkney, founding president and CEO of the Historic Hampton House Community Trust, deserves much of the credit for saving the motel. As a young woman, she spent many nights dancing in the jazz lounge and eating in the 24-hour restaurant.

“We would leave work, go home, and get dressed to go to Hampton House,” Pinkney tells New Times. “It was an exciting place, and you could meet so many different people. It really was an important part of the community, and all the celebrities made it even more exciting.”

Pinkney hopes One Night in Miami will reignite interest in Hampton House and encourage financial support for its operating expenses and community-engagement projects.

Marketing director Edwin Sheppard, who left the Fontainebleau to work for Hampton House, is too young to remember the motel’s belle époque. Still, he exudes an effusive passion for its history. He also sees the film as an exciting vehicle for broader conversations around historical preservation and education.

Despite 2020’s unprecedented challenges for the film industry, One Night in Miami debuted to great acclaim at Venice Film Festival and Toronto International Film Festival, among others.

“This movie is a love letter to the Black man’s experience in America,” King writes in her director’s statement. “It was a chance to show these icons as men first, as brother first.”

The fact that the segregation-era Hampton House functions as the film’s safe space and inner sanctum is a fitting tribute to the Miami institution.

One Night in Miami. Starring Kingsley Ben-Adir, Eli Goree, Aldis Hodge, and Leslie Odom Jr. Directed by Regina King. Written by Kemp Powers. 114 minutes. Rated R. In theaters now and streaming on Amazon Prime on Friday, January 15.