Dr. Lord Lee-Benner has seen the dark side of the Sunshine State: its schizophrenics, neurotics, addicts, depressives, illiterate bipolars, disturbed teens, even psychotic ex-ministers.

Many of the indigent patients who come to see him at Community Health Center of West Palm Beach, a nonprofit clinic where he volunteers as a psychiatrist, just want a pill or a refill of psych meds prescribed by a previous doctor.

But that doesn't fly with Lee-Benner, an 85-year-old Korean War vet who says he's a prince.

"There are certain cases where I agree they need medication," Lee-Benner says. "But I tell others: 'You have to show me that you're going to do something for yourself. I expect results.' It requires tough love sometimes."

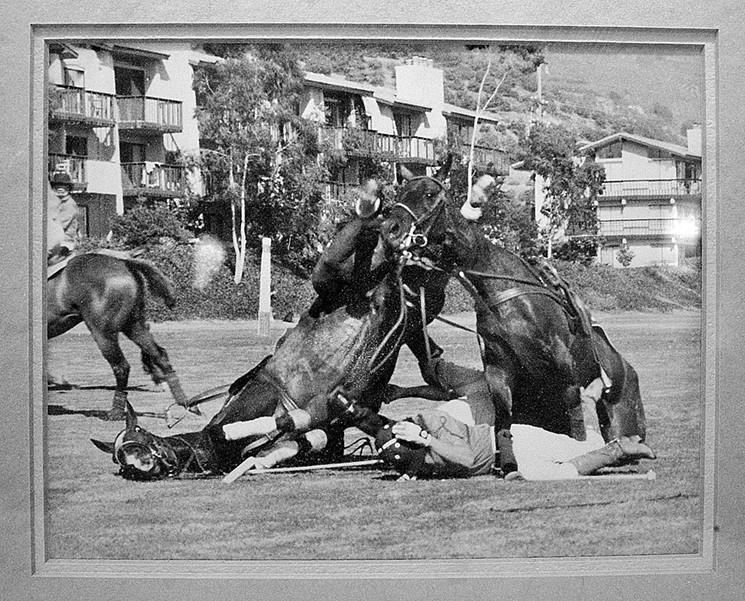

Visit his home office at his West Palm penthouse condo and you'll find a framed photo on a shelf above his desk that shows him falling from a horse during a polo match 20 years ago. In another, he poses shirtless in black short-shorts with the physique of Adonis.

Watch the doctor's Dorian Gray-like biography morph into something else completely.

tweet this

"Of course, I've gone downhill since then," he laments, staring at the photos on a recent afternoon. Downhill, though, is a relative term. Despite his age, he's prone to wisecracks. Today he's dressed in white linen pants and a sleeveless white linen shirt that reveals defined shoulders and impeccable posture.

You haven't heard of Dr. Lee-Benner. He keeps a low profile. Continue scanning the row of photographs on his shelf and you'll understand why, as you watch the doctor's Dorian Gray-like biography morph into something else completely. Older, grainier photos show him in front of splendid forts and mausoleums and at his wedding in the gardens of a royal palace. It all hints at a backstory he says he's kept hidden until now. It's a tale of kidnappings and orphanages, of turbaned impresarios and British MI6 assassins (who wanted him dead), of Miami rags and international riches.

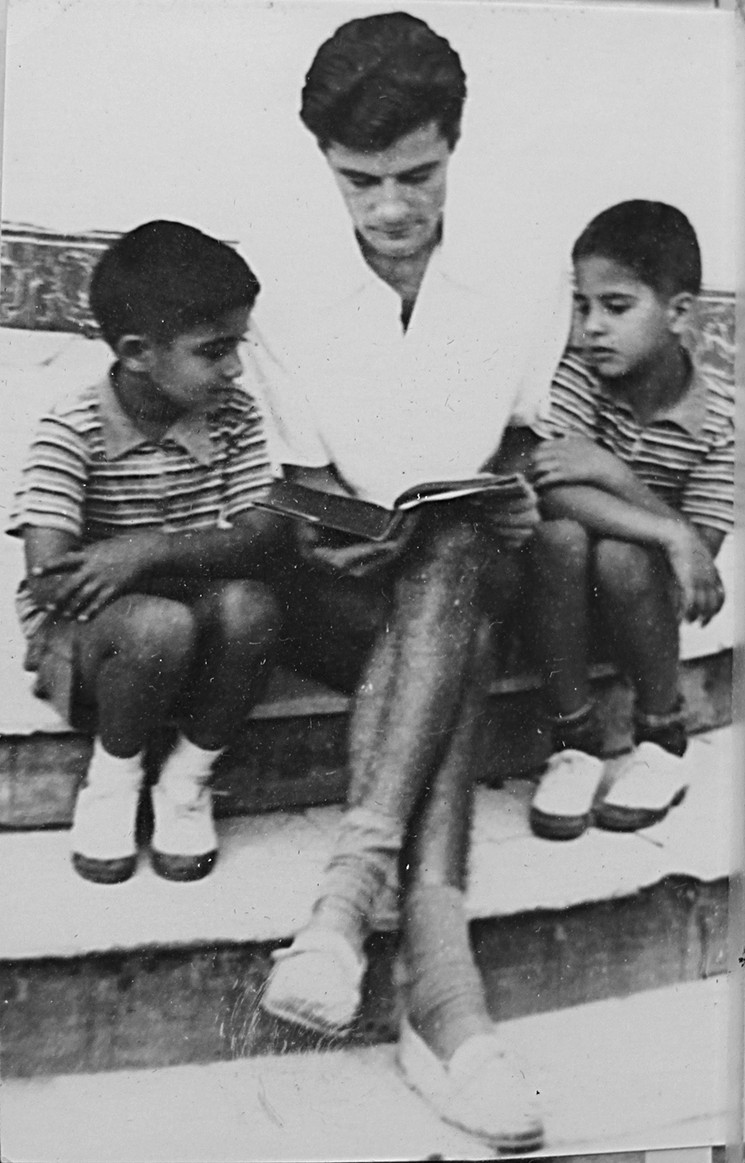

Lee-Benner was born in Chicago in 1934. His first four years are a blur, but he has vague recollections of singing and dancing with his younger brother for small crowds and being shuttled around the country in buses and trailers along with a cast of carnies: the Tattooed Lady, the Indian Rubber Man, Priscilla the Monkey Girl, the Fat Man, giants, and erotic dancers.

His parents, both traveling performers, told him he was an extra in Hollywood films starring Errol Flynn and Gene Autry, but he can't recall those experiences or find his name in the credits.

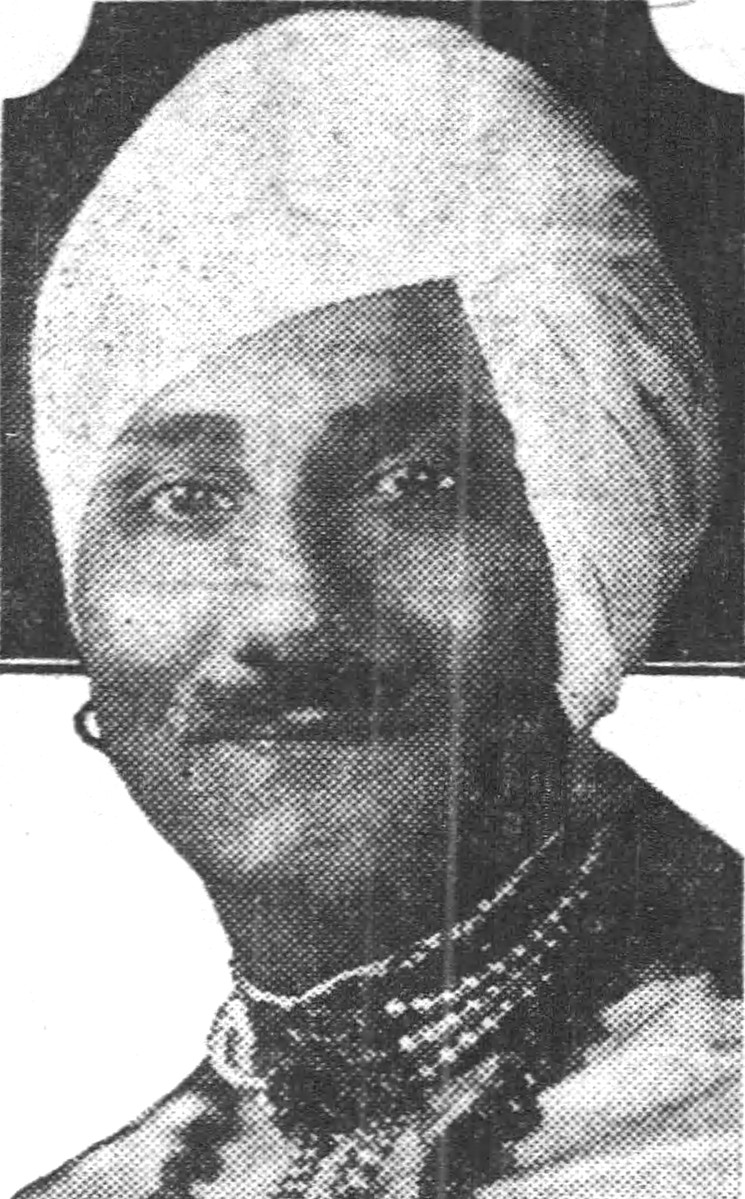

Years earlier, in 1920, his father, Khaja Monavor Shah, had arrived at Ellis Island on a ship from England. The ship's manifest, which is still listed on a news database, says Shah was 22 years old. News articles from across the nation, also discovered online, show that by the end of the '20s, Khaja Shah had become Prince Shah Babar. He is variously described by the papers as "a mystic," "mind-reader," "fortune-teller," "psychic," "miracle man," and "prophet with telepathic powers."

The 36-year-old Babar told Constance a riveting story of royal exile.

tweet this

A dashing ladies' man, Babar performed shows to packed houses where he read minds and advised audience members on love, work, and personal dilemmas. He often held ladies-only shows and wrote an advice column for The Montgomery Advertiser, an Alabama newspaper, in which he sometimes advised women on how to keep their men happy: "Always be sweet and devoted to your prospective husband and endeavor to show a constantly charming smile, whether you are really cheerful or not."

Like any good hustler, he eventually made his way to Miami, where he met an 18-year-old bohemian showgirl, Constance Reardon, who lived with her sister and widowed mother in Miami's Lemon City, now called Little Haiti. The 36-year-old Babar told Constance a riveting story of royal exile.

Babar, Lee-Benner says, told his bride-to-be that he was born in Kashmir, India, and was the great-grandson of Zofar Bahadur Shah II, the last "Mughal" emperor of India. The Mughals were Indo-Persian Muslims who ruled India for more than 300 years. In 1858, English imperialists took control of India, exiled the emperor, and killed his heirs. Some heirs, however, escaped. In the decades following, the British continued to hunt and kill them to prevent their return to power. When the Brits discovered Babar in India in 1920, he made a last-minute escape through a bathroom window, jumped a ship to London, where he eluded authorities, and fled across the Atlantic. (The existence of Bahadur Shah and all of that history, at least, is confirmed by the BBC.)

In America, the Roaring Twenties were just kicking off, and Babar found a nation of prosperous people hungry for the new and the exotic. He donned a turban and gem jewelry and hit the road. By 1934, when he met Constance in Miami, he was thriving, even though the rest of the country wasn't. The two married and began traveling Depression-era America together, performing vaudeville, burlesque, and mind-reading shows.

Dr. Lee-Benner was born the year those travels began. His younger brother, Sirdar, was born a couple of years later. The doctor describes his father as a "bullshit artist" who learned to "live by his wits." But, he says, the princely part of his father's tale is legit. British MI6 agents eventually discovered him living in the United States.

"We were hunted and chased for years," he says. "My brother and I were kept hidden, living in boarding schools, or placed in one foster home after another. I have memories of living for a time in a convent in Pittsburgh. Also, our names were changed five different times to keep us from being detected."

His parents didn't remain married for long, and he eventually went to live with his aunt and grandmother in Miami, where life as a dark-skinned boy in the pre–civil rights South wasn't any easier, he says. "People called me a nigger. I had to fight my way home from school every day."

At home, there was no money and even less affection. "They beat us," he says, "my grandmother, my aunt, my mother, when she was around. I didn't have a warm, cuddly childhood. No comfort. No security. Just madness and abuse."

His mother, he says, suffered from mental illness, and men came and went from their lives. There was one good man, though: Roger Lee-Benner. He married Constance and adopted her two boys. The marriage lasted only six months, but it was long enough for the kids to take his surname, which Dr. Lord Lee-Benner says protected them from the British and from later prejudice against people with Asian names.

By 1947, the threat ended when India gained independence from British rule. Lee-Benner's father, Prince Shah Babar, resurfaced in Miami a few years later and took him and his brother to the Indian embassy in Washington, D.C., to formally present them as heirs. Members of India's emerging government, Lee-Benner claims, came to the United States before that to ask his father if he would "care to return to assume the throne." He declined and disappeared from the boys' lives again shortly thereafter, never to be seen again.

Newspaper archives suggest that middle age, World War II, and a more sophisticated public ended Babar's career as a lady-loving, mind-reading impresario. He owned a gear-manufacturing company in Detroit and bought and managed a trailer park in Texas for a while. He eventually got into the import-export business. In 1984, he died in Orlando at the age of 86.

His death, Lee-Benner says, reshuffled the family line: "My father was crown prince, which I am now. My title is 'His Imperial Highness the Crown Prince of the Mughal Dynasty.'"

Complicating Lee-Benner's tale, however, is the fact that many other people also claim to be descended from the royal family.

Former Harvard professor of Near Eastern Studies, Wheeler Thackston, says he can neither prove nor disprove Lee-Benner's lineage. But he notes that Bahadur Shah II, the last Mughal emperor, had 22 sons and 32 daughters, most of whom had offspring. So, though Lee-Benner might be descended from the emperor, he's hardly alone.

Lee-Benner counters that the British murdered all of those offspring except for his father's father, who was secreted away by family servants. "I found this to be a matter of record in the archives of the [then-named] Museum of History in Delhi, which I visited in 1984," he says.

Online sources aren't clear on which family members, if any, escaped the British, but people claiming direct lineage to the emperor have surfaced in places ranging from Detroit to Calcutta. In 2009, a group of prominent Indians launched a trust to trace Mughal descendants and determine how many royals actually remain. Their results have not been made public.

Meanwhile, Professor Thackston is skeptical of Lee-Benner's claim he was hunted in the mid-1900s, questioning why the British would have feared the descendants of an emperor whose throne was eliminated in 1858. And "the idea of [India's emerging leaders] offering the throne to anyone strikes me as sheer fantasy," he says.

Professor Thackston is skeptical of Lee-Benner's claim he was hunted in the mid-1900s.

tweet this

Lee-Benner explains that both events were covert and would not have been publicized or have made it into the historical record.

Yet what Lee-Benner lacks in royal documentation, he makes up for with professional credentials. After graduating from Miami Edison Senior High, he spent 13 years in the Navy, and fought in the Korean War, before graduating from the Medical University of South Carolina and completing nine years of postgraduate study in neurosurgery, psychiatry, psychoanalysis, neurology, radiology, and neuroendocrinology.

He mostly applied that training in the field of anti-aging, where he says he pioneered both the use of human growth hormone in adults and of antioxidants — nutrients thought to combat certain kinds of cell damage.

He doesn't like the term "anti-aging,' though. "It's a misnomer because there's no such thing," he says. And although he uses it because he "can't fight popular culture," he has distanced himself from the unregulated, "charlatan," anti-aging industry and even from organizations he cofounded, such as the American Academy of Anti-Aging Medicine (A4M).

Meanwhile, he has remained preternaturally young himself, playing professional-level polo well past his prime.

As a kid, he had earned a dollar per day exercising and showing thoroughbreds at the Hialeah Race Track. Then, during the Korean War, he discovered polo while stationed in Bangkok and took it up seriously after returning home.

"Eventually, I got noticed by some wealthy people, who sponsored me," he says. "I started being an international polo player all over the world. I could barely spend time practicing medicine. I was too busy playing polo and living it up with whoever my benefactor was — you know, rich old ladies or whoever wanted to buy me horses."

He moved to California in the mid-'70s for the year-round polo scene and began traveling to Europe and South America between matches to buy and sell racehorses. He made a small fortune in the then-thriving horse trade and partied with the rich and famous at polo clubs around the world.

But that life came to an end with the global recession of the early '80s. "You couldn't write off horses as a hobby anymore," he says. "Interest rates went up to 18 percent. I had huge loans, and all the banks foreclosed on me and I basically went broke. So I had to go back to being a doctor."

He still played polo whenever he could, even into his mid-60s, but his professional days were over.

In 1984, he opened the Lee-Benner Institute of Aging Control and Nutritional Medicine in Newport Beach, California, and became known as the "Longevity Doctor" — mostly by preaching the benefits of caloric restriction, nutritional supplementation, exercise, and, if necessary, hormonal balancing. In 1992, California Magazine, published by UC Berkeley, dubbed him the "Lord of Longevity."

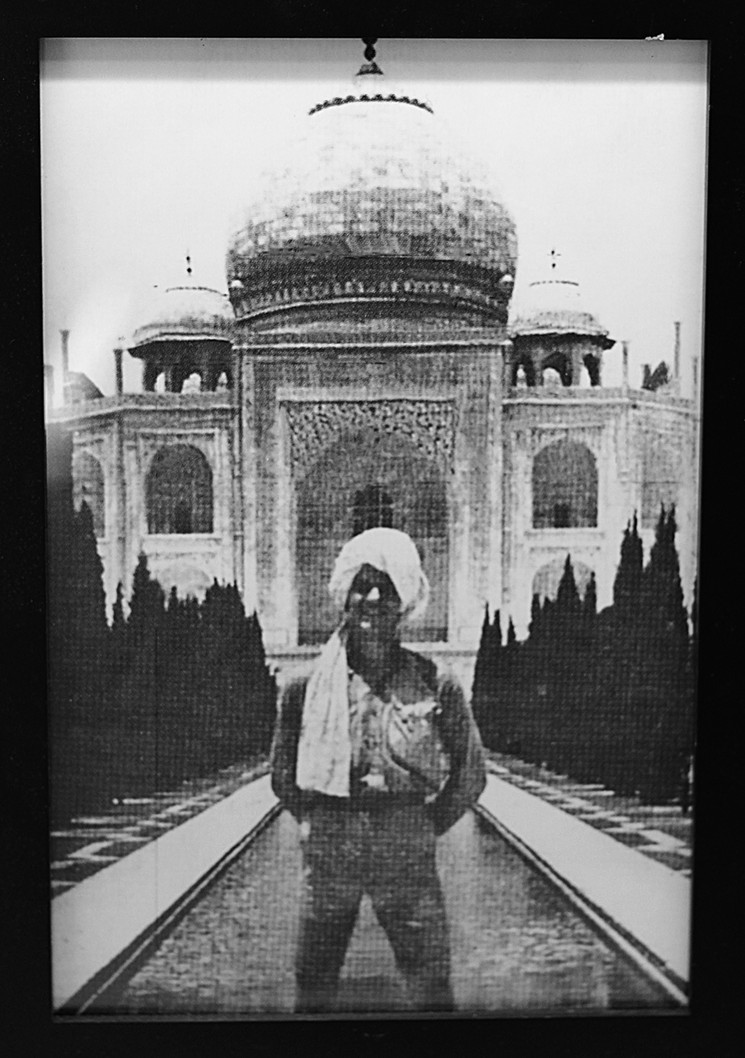

He visited India for the first time in 1984, where he married his current wife, Blake, an American artist. It wasn't his first marriage. How many were there? It's a sore subject. But with Blake, he says, "we saw each other across a crowded room at the Santa Barbara Polo Club, and that was it."

"We had a wedding ceremony in my grandmother's mausoleum, the Taj Mahal," Lee-Benner says, referring to the world-famous Mughal structure. "Then we flew up to my ancestors' palace in Srinagar, Kashmir, to have a formal Persian wedding ceremony there."

In 2014, he returned to South Florida. These days, he helps the mentally ill indigent. He says he's the only psychiatrist in Palm Beach County to do so for free. "I do it for fun," he says. "It's my antidepressant for the day."

Some patients, he believes, can be treated with nutrition. Instead of giving them a tranquilizer, he asks, "What did you have for breakfast?"

"A lot of them are depressed or are anxiety cases because they don't know how to eat," he explains. "If you don't feed the brain properly, it sends down emergency signals, and that creates anxiety, shortness of breath, palpitations, fatigue, even phobias."

Nutritional pharmacology, a term he says he coined in 1984 to describe his approach to mental and physical wellness, underpins his treatment of South Florida's mentally ill. It's also the source of his own relative youthfulness.

"A lot of them are depressed or are anxiety cases because they don't know how to eat."

tweet this

George Papadimitriou, executive director of Community Health Center of West Palm Beach, the faith-based, charitable clinic where Lee-Benner volunteers, describes the doctor as "an amazing man with an altruistic spirit... [who] has not only impacted, but saved the lives of hopeless individuals who had nowhere else to turn."

Meanwhile, Lee-Benner rarely talks about his family background. Americans, he says, don't care much for claims of aristocracy. And India, now the world's largest democracy, is unlikely to come courting any long-lost princes.

How many princes there are, and where they are, is difficult to know. But Lee-Benner, at least, has no doubt about his identity. At home, surrounded by books, DVDs, and mementos of India's greatest dynasty, he mentions a photo of the last Mughal emperor. It was taken in 1858, when the emperor was 83 years old. "I'm starting to look just like him," Lee-Benner says.

"For what it's worth," he adds, "I am the last Mughal."